Dorothee Richter: Artists and Curators as Authors – Competitors, Collaborators, or Teamworkers?

World of Art | Year 14 | Reflections and shifts in curatorial, critical and artistic practices

Thursday, March 15, 2012, at 7 p. m.

MGLC, Ljubljana

This paper discusses artistic and curatorial authorship, and attempts to situate it within history. Are artists and curators competitors for authorship in the fine arts? Have curators adapted procedures of artistic self-organisation, and if so, with which consequences? Or are artists and curators collaborators in an area in which attributions are uncertain, and therefore also more flexible and negotiable? I will discuss these questions based on several concrete historical examples:

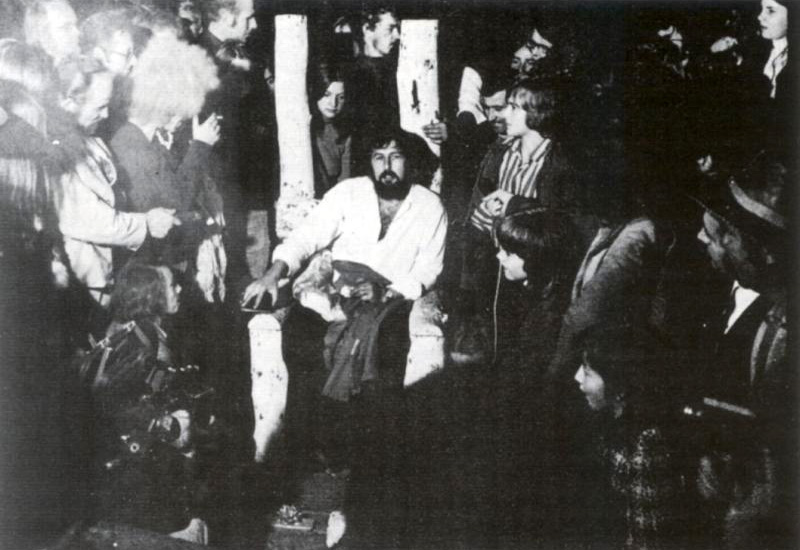

- Photography of Harald Szeemann at Documenta 5

- Case study The Fluxus artists and their struggle for the power of definition

- Case study: The Curating Degree Zero Archive as an attempt to negotiate and hold in suspense the relationship between artists and curators

Harald Szeemann on the last day of documenta 5 (8 October 1972), black-and-white photograph taken by Baltasar Burkhard

I will follow in this paragraph an argument, that Beatrice von Bismarck has developed[1]: The pose adopted by Harald Szeemann on the last day of Documenta 5 established the occupational image of the authorial curator as an autonomous and creative producer of culture, who organised exhibitions independently of institutions as Beatrice von Bismarck has first pointed out. For the first time ever in the history of Documenta, an individual curator single-handedly defined its theme, calling the central section of the exhibition ‘Individual Mythologies’ (within the overall exhibition theme ‘Questioning Reality – Image Worlds Today’). Szeeman was solely responsible for the selection of artists, while previously artists had been chosen by a committee of art historians, politicians, and association chairmen. Szeeman was appointed ‘General Secretary of Documenta 5.’[2] Image 1 operates within my argument as a switch point onto which I fasten various attributions concerning this figure. I will draw several historical comparisons to reveal the underlying process of signification. The image unmistakably reveals a specific arrangement of power: a cast figure enthroned amid a group of persons is a highly traditional kind of image composition. In what follows, I will discuss three pictures selected at random from Dumont’s Encyclopedia of Arts and Artists. Each of these depictions adheres to the basic pattern, since the restaging of this pose resonates with previous patterns of meaning. I will comment only briefly on the image composition of these works, ignoring other aspects[3] because I will especially looking into the appeal character of images in the political sphere.

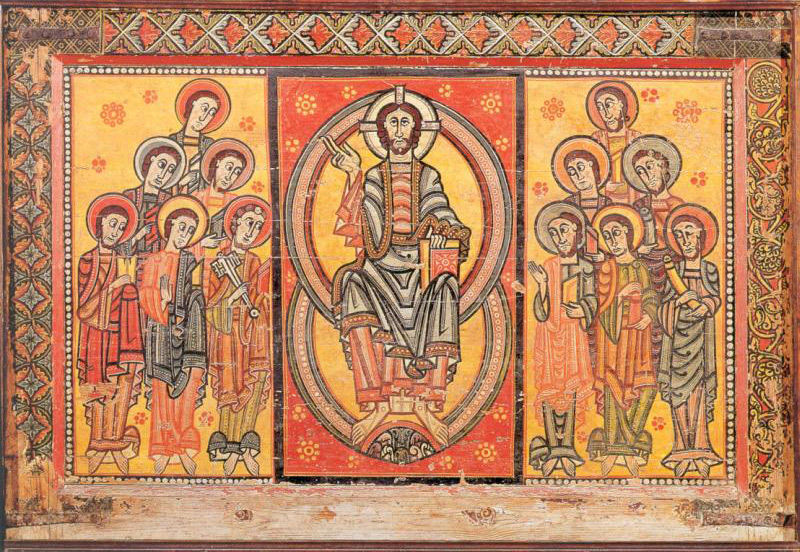

Spanish Antependium (alter substructure) with Christ in the Mandorla and with the Twelve Apostles, around 1120, Barcelona.

The meaning of this image arises from its interaction with a divine service, in that it serves to instruct and situate the congregation. Its primary purpose is to depict Christ as a God who has become human. The rigid composition of the image and its schematic figures make it clear that a firmly established hierarchy exists, in which relations are entirely formal and impersonal. The arrangement of power is rigid.

The proportions of the figures clearly establish and substantiate an obvious hierarchy between divine creation and mortal humans. One figure stands at the centre of the picture. While the arrangement of figures and their proportions vest the central figure with power and authority, God is at the same time also human. The picture presents itself as a truth, hierarchically situating us as viewers standing in front of it and accepting instruction.

Duccio: Maesta 1308−1311, Tempera on Poplar (Antependium= altar substructure)

Duccio’s Maesta also fulfils a cultic function. Its composition implies worship and veneration, specifically the veneration shown towards a woman with a male, God-like child on her lap. The sheer size of the Mother of God removes her from the human mortals turning towards her and the child. She holds the child in her arms and lowers her gaze, whereas the baby Jesus looks with authority out of the picture into the world. Like the previous picture, Duccio’s also hierarchically situates its viewers, who can to a certain extent identify themselves with the gesture and movement of the worshippers in the picture.

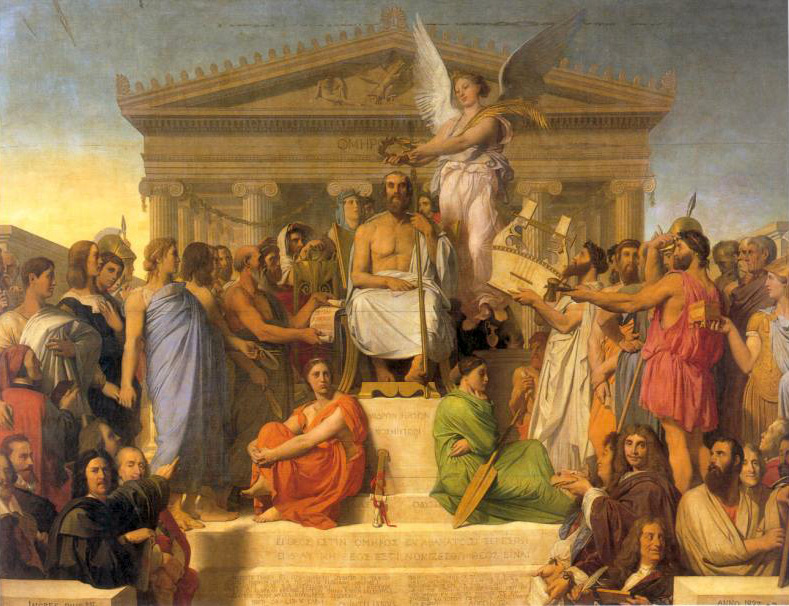

Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, The Apotheosis of Homer, 1827, 3.86 x 5.15

The Greek poet Homer is the central figure in Ingres’s The Apotheosis of Homer (1827). Clearly apparent in the painting is the attribution of an ingenious spirit bestowed upon the poet by divine powers. Inscribed in this arrangement, moreover, are additional concepts and effects of gender difference, which since the Renaissance have constructed the male subject as the subject of central perspective. The female muses sit at the poet’s feet. The specific dynamics of composition are such that the painting radiates beyond its edges and involves us in the events shown. The figures in the foreground turn towards us, appealingly, and direct our attention to the poet in a kind of substitutional testimony. As viewers, we close the circle around the poet, albeit on a much lower level. We complete the painting as it was, whose composition is obviously meant to address and include us.

Let’s return back to the Image 1.

Seen thus, Harald Szeemann’s pose is a distinctive positioning, based on historical schemata, especially of the curator as a god/king/man among artists. Comparable to earlier visual demonstrations of power, this picture also endeavours to position its viewers, plainly appealing to their attention. Viewers are thus positioned opposite a scenario in which the artists form a clearly lower-ranking group as the curator’s adepts. Szeemann’s casual and sprawling pose makes it clear that here is someone who can take liberties. As viewers, we occupy an even lower hierarchical position than the artists; we are situated as eyewitnesses of a spectacle, not as members of a bohemian community. Nevertheless, our role is to provide affirmation.

Beatrice von Bismarck has observed that Szeemann’s curating of When Attitudes Become Form, an exhibition that he organised as director of the Kunsthalle Bern in 1969, firmly established his position and recommended him to convene Documenta 5.[4] In 1969, Szeemann voluntarily resigned as director of the Kunsthalle Bern to found his own agency. He called the agency ‘Agentur für geistige Gastarbeit im Dienste der Visualisierung eines möglichen Museums der Obsessionen (Agency for Spiritual Guest Work in the Service of Visualising a Possible Museum of Obsessions)’. He didn’t register the agency and according to Sören Grammel it had no legal status. Szeemann described the curator as a ‘custodian, sensitive art lover, writer of prefaces, librarian, manager, accountant, animator, conservator, financier, diplomat, and so forth.’[5] He positioned the Museum of Obsessions as an ideal construction, as a curatorial concept. Employing the notion of the museum as a fictional institution, Szeemann brought it close to the actually existing institution as part of the institution of art, implicitly positioning himself as a museum director. Such positioning at the same time distanced the Museum of Obsessions from actually existing art institutions. While Sören Grammel’s study of Szeemann’s authorial position argues that ‘agency’ points to a division of authorship in the production process, I would like to suggest that the term by all means implies hierarchy, and thus largely revokes the notion of divided authorship. Agencies have executives who are granted the right to commercially exploit their products; − agency profits, however, belong to executives, not to staff.

Szeemann’s demonstration of power did not unfold without conflict. How actually did the dispute between the artists and the exhibition curator happen? The following remarks were made by Robert Smithson, Szeemann appropriated the quote insofar as Smithson’s article appeared in the exhibition catalogue for Documenta 5:

‘Cultural confinement occurs when a curator thematically limits an art exhibition instead of asking the artists to set their own limits. One expects them to fit into fraudulent categories. Some artists imagine that they have this mechanism under control, while in reality it controls them. Thus, they support a cultural prison house that escapes their control. The artists themselves are not restricted, but their production most certainly is. Like asylums and prisons, museums also have inpatient departments and cells, namely neutral spaces that are called ‘galleries’. In the gallery space a work of art loses its explosiveness and becomes a portable object cut off from the outside world (…) Could it be that certain art exhibitions have become metaphysical scrap yards? (…) The curators as wardens still depend upon the debris of metaphysical principles and structures because they know no better.’[6]

In retrospect, Szeemann commented self-confidently on his function as a warden, selector, and author: ‘Nevertheless, this was hitherto the most comprehensive attempt to turn a large exhibition as the result of many individual contributions into something like a worldview (…).’ He formulated ‘Individual Mythologies’ as a ‘spiritual space in which an individual sets those signs, signals, and symbols which for him mean the world.’[7] Admittedly, Szeemann’s view focused entirely on himself as author, and he considered the exhibition to be an image of one single worldview. While Daniel Buren participated in Documenta 5 as an artist, his contribution to the exhibition catalogue criticised the absorbing gesture of Szeemann, the meta-artist:

‘The exhibition is tending increasingly towards the exhibition of the exhibition as a work of art and no longer as an exhibition of works of art. Here it is the Documenta team, under Harald Szeemann, that is exhibiting (the works) and presenting itself (to criticism). The works on display are spots of colour – carefully selected – of that picture that each section (hall) has assembled as a whole. There is even an order prevailing in these colours, since they have been targeted and selected based on the concept of the hall (selection) in which they exhibit and present themselves. Even these sections (castrations), which are – carefully selected – spots of colour of the painting that the exhibition is working out as a whole and as a principle, become visible only if they surrender to the organiser’s protection, he who unites art by equalising it in the box screen that he rigs up for it. He (the curator) assumes responsibility for the contradictions; it is he who veils them.’[8]

Even though exhibitions had been deployed since the French Revolution as new overall contexts of signification, capable of ideologically representing the state, nation, or the bourgeoisie, the focus on a single curator organising an exhibition was new. Seen thus, the photograph of Szeemann marks a turning point in the discourse and becomes effective alongside the resonant meanings handed down over time. The curator became a meta-artist. Which position were artists chased from in the process?

Walter Grasskamp’s history of Documenta might give us some idea in this respect. Documenta is a paradigm of the production of art history, because in discursive terms it represents the most powerful exhibition enterprise of the post-war period in the German-speaking world. By mounting this large exhibition, post-war Germany demonstrated its endeavour to overcome Nazi ideology, a nationalist conception of art, and the National Socialist aestheticising of politics. The Nazi regime’s aestheticising of politics had occupied large parts of public representation and thus also of public consciousness.[9] Seen thus, the early Documenta exhibitions were a means of, and evidence for, the re-education of the German people. Similar events occurred at the Venice Biennale: in 1958, Eberhard Hanfstaengel, the German commissioner, presented as national representation a retrospective of the work of Vassily Kandinsky at the German pavilion (a neo-classical pavilion previously converted by the Nazis). Grasskamp notes that the exhibition (he refers to the Venice Biennale) ‘signalled to an international audience the intention of the Federal Republic of German to adopt previously banished and persecuted modern art as state craft.’[10]

The Heroes of an Exhibition: Artists as Citizens

Walter Grasskamp has pointed out that Documenta 1 placed artists centre stage. Besides the actual catalogue images, the catalogue for Documenta 1 featured an architecture section and ‘a highly odd image section containing 16 pages, which the table of contents referred to quite laconically as images of the artists. Among others, this section included images of Picasso, Braque, Leger, the Futurists, Max Beckmann, and other participants either at work in their studios or taking up a pose. No artwork shown at the inaugural Documenta can be more typical of the particular reception of art at the time as this slim collection of images, in which modern artists are explicitly presented as heroes. These hero images share an aura of seriousness and respectability.’[11]

Documenta 1, 1955

The entrance hall was also framed with portraits of artists, whose faces welcomed exhibition visitors. The portraits seemed rather like images of politicians or bankers, thus presenting the artists as citizens, as men clothed in suits and ties. They personified the new heroes, who replaced military and dictatorial leaders. The portraits were hung almost at eye level, from which we can infer a visualising of egalitarian principles. The Documenta 2 catalogue lacks a concentrated glorification of artists, as Grasskamp observes: ‘Instead, the portraits of the artists are interspersed in the catalogue section, and could hardly be more pathetic, in some cases even worse. Such portraits are completely missing from the Documenta 3 catalogue; as if one had sought to correct an embarrassing lapse, the works alone now stand for the name, and the same applies to the catalogue of the fourth Documenta.’[12]

It should be stated, that instead showing the prosecuted or murdered artists it was a kind of evasive gesture to show the now called classic modernism as an internationally accepted style.

Documenta 5 however no longer features any serious bourgeois portraits, but instead a hierarchically structured group, which nevertheless amounts to a rather anarchic overall picture. The dispute between artists and exhibition makers seemed to have been settled for the time being. The curator was now not only the ‘warden’, but above all the figure subsuming the exhibition under one single heading. He prescribed a certain reading of the works, the title became the most distinct (succinct) version of a programme, and his name emerged as the discursive frame. Szeemann had thus wrested the naming strategy and labelling from the hands of artist groups and had successfully transferred the exhibition into the economic sphere. For visitors, the title Individual Mythologies blended with the individual works and thus predetermined meaning – with the works forming small parts of a mythological narrative. Where, however, did the anarchistic bohemianism seen in the photograph come from? Which artistic strategies were possibly (iconographically) adopted between 1955 and 1972, which new forms of organisation preceded this gain in power, and which new forms of a creative potential were tried out beforehand?

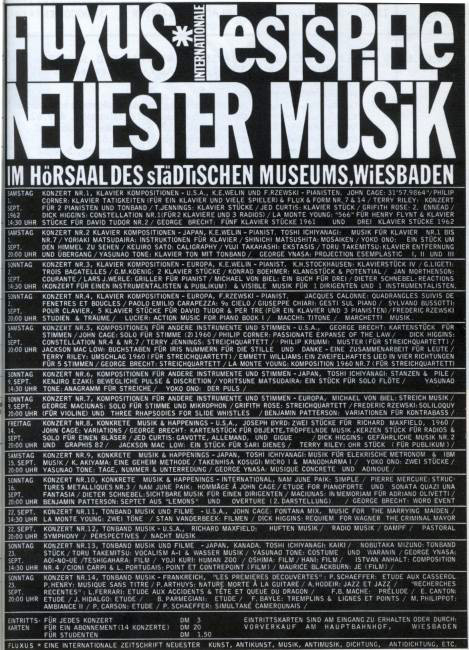

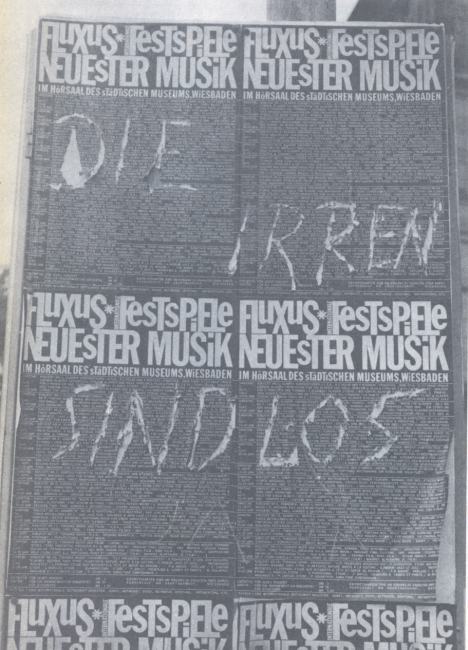

Poster, Wiesbaden Festival of New Music, 1962

This poster announces the first Fluxus festival held in Wiesbaden in 1962, that is, 10 years before Szeemann’s appointment in Kassel.

FLUXUS – Artists as Organisers

The 1960s witnessed a growing number of artist groups, including Fluxus, Viennese Actionism, the Situationists, the Affichistes, the Destruction Art Group, the Art Workers’ Coalition, the Guerilla Art Group, Nouveau Réalisme, the Letterists, the Happenings, and the Gutai group. Each movement developed under specific social and historical conditions.[13]

In the German-speaking world, especially Fluxus and the Viennese Actionists became well known, as well as the Happenings, which were, however, not strictly distinguished from the two other movements. The reformulations introduced by these revolutionary art movements imply an altered positioning of art towards politics, and of the private sphere towards the public. They exploded genre boundaries, questioned the author’s function, and radically changed the production, distribution and reception of the fine arts. Artist groups organised their own opportunities for public appearances. Their scores were performed jointly and differently in each revival; they took charge of distribution, of publishing newsletters and newspapers, and of establishing publishing houses and galleries. Audiences were now directly involved and subject to provocative address. The inversion of terms instituted by Fluxus, by mapping their methods of composing music onto all aspects of the visual, made it possible to consider everything as material and as a basis for composition.[14] They challenged hitherto prevailing cultural hegemony and manifoldly anticipated on a symbolic level the 1968 student riots and protest movements.

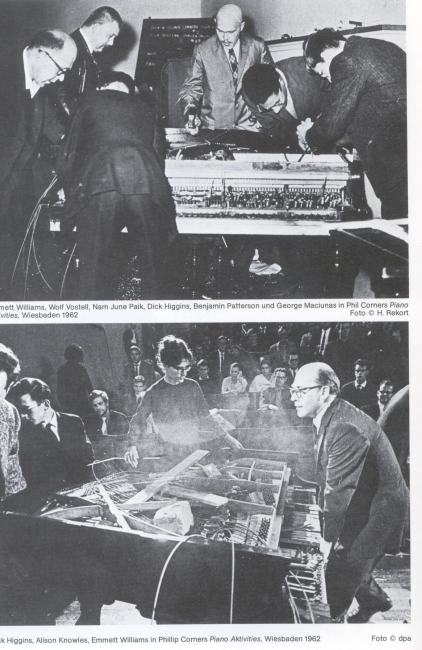

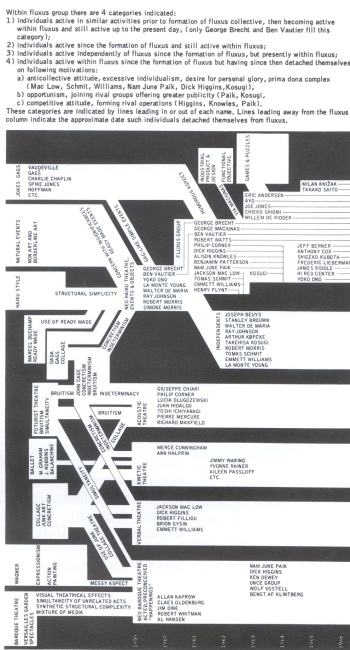

Wiesbaden Festival of New Music, Pictures of Philipp Corner’s Piano Piece, September 1962−1

In Philipp Corners Piano Piece, an alternating number of performers dismantled the piano on the subsequent weekends of the festival; the event score suggested various activities with the piano, such as ‘drop objects on strings on other parts of piano or draw chains or bells across, act in any way on underside of piano’[15] (two out of nine instructions). The individual parts of the instrument were auctioned at the end of the festival.

Wiesbaden Festival of New Music, Pictures of the Philipp Corner’s Piano Piece, September 1962−3

‘Fluxus’ spread via newspaper reports and photographs, and was thus known to a large number of people. This black-and-white photograph shows eight persons of whom six are intensely busy with a piano while two are sitting at the right edge of the picture observing proceedings. The first impression of the photograph is one of extreme artificiality. It looks so forcefully composed that one at first believes it is a photomontage. The hard, high-contrast lighting and the jutting of a ledge or wall into the picture on the left makes it seem decomposed by a series of cuts. Its upper right part looks curiously blurred and cloudy, the traces of irregular image development and its coarse-grained character convey spontaneity and as it were the ‘documentary’ as a subtext, since its technical development is somewhat amateurish.

The photograph has obviously slid from a horizontal position, thus adding to its dramatic effect together with the hard shadows of the figures.

The opened-up piano, into which we see from above, reveals its partly wrecked inner life. The arrangement of the figures around the piano recalls images of medical operations or anatomy classes from art and film history. This concentration and the serious faces of the actors support these associations. The seriousness of those involved also reminds one of children dismembering an animal or disassembling an alarm clock; it seems quite obviously incommensurate with the dismantling/destroying of a piano. The two spectators on the right side of the photograph are the only figures facing the photographer or rather the present-day viewer. Both are smiling rapturously, almost ecstatically, and their expression reminds me of the concept of ‘jouissance’, that is, of (female sexual) pleasure.

The actors destroying/disassembling a piano can be easily read as an attack on one of the symbols of the bourgeois conception of education and morality. The photograph (taken in 1962), which appeared on the front cover of a catalogue in 1982, must have been considered an enormous affront against the bourgeoisie and its values when it was taken in 1962. Justin Hoffmann has also suggested that in the 1960s art frequently involved the destruction of musical instruments, for instance Nam June Paik’s One for Violin, Terry Riley’s Guitar Piece, and so forth. Hoffmann sees this as a destruction of the status symbols of bourgeois culture.[16]

In retrospect, we can read the piano as a symbol that just as classical literature provided the bourgeoisie with a certain noble possibility to withdraw from the boredom (humdrum) of everyday politics, that is to say, with an innocent ‘that is, blameless’ retreat from the memories of Nazi crimes against humanity and the latent question of guilt. Without doubt, the piano is a complex symbol in post-war Germany. Those advocating reactionary positions have repeatedly had recourse to timeless cultural values. One prominent example is Hans Sedlmayr, who claimed that he had never adopted another position other than harmony and timeless values.[17]

Fluxus artists took up educated middle-class concepts in both their choice of venues (museums, universities, galleries, concert halls) and the terms employed in their events, such as score, composition, symphony or concert – only to subsequently subvert them. Silke Wenk has shown that in the post-war period the need of Federal Germans for a clearly structured order organised in terms of stable values, which found only partial expression in political discourse, was displaced onto high culture.[18] Hierarchised high culture therefore appears as a refuge from the collapse of a collective nationalist identity at the end of the Hitler regime and the aggressions and sense of guilt bound up with this breakdown. Adorno, a contemporary of the Fluxus movement, concluded ‘that secretly, unconsciously, smouldering, and hence particularly powerful, those identifications and the collective Nazism (here nazi-ideology) were not destroyed at all but continue to exist. The defeat has been ratified within just as little as after 1918.’[19] The destruction of the piano under the ‘misleading’ headings ‘concert, New Music, score, etc.’ shattered precisely this bastion of retreat to ‘timeless’ hierarchised high culture. The Fluxus actions revealed a fissure in the imagined unassailability and sealing off of this cultural sphere. When gazing into this fissure, the contemporaries perceived an atmosphere of gloom: excessive sexuality, guilt and violence.

Already in 1965, Fluxus artists began publishing sarcastic articles that had previously appeared in the Bildzeitung (Germany’s major tabloid) and middle-class feuilletons, together with photographs of their performances and reports penned by the artists. Reprinting a Bildzeitung article, a paper known for its right-wing tendencies, in an Fluxus publication as it were situated the artists’ actions as left-wing and potentially revolutionary. The description of the audience in this article as ‘bearded young men, demonically looking teenagers, and elderly women’ carries sexual connotations. Precisely those persons most likely to be of an age in which they would be living in a well-ordered sexual relationship, namely a middle-class marriage, are conspicuously absent from such a description. Even the ‘elderly women’ appear to have come without elderly men. Each of the groups mentioned implies a certain sexual openness, not to mention availability. The suspicion of sexual debauchery, at least by way of allusion, underlies the description as a subtext. Press comments varied from mere boredom to derisive comments. Reprinting the articles in a documentation published by artists foregrounds the narrow-mindedness of the press and buttresses the mythologisation of Fluxus actions as those of a protest movement. Moreover, conducting a negative discourse on a work of art also produces meaning (and ultimately enhances its value), as the artists realised.[20]

One further connotation of the piano is virginal innocence, since learning to play the piano was still considered part of the virtues of the unmarried daughters of middle-class families. Since the eighteenth century, rooms were increasingly classified along various parameters: public vs. private, work vs. recreation, and male vs. female. In this respect, we can bear in mind the determining of gender roles, which assigned middle-class women to an extremely restricted sphere, comprising not only sexual unfreedom but also a general subordination to their husbands’ needs and affairs, as well as economic dependency.

The aggressive assault of the Fluxus artists resembles a violent prising open: the piano seems naked, innocent, and raped. The actions of the all-male attackers is brutal; the only figure whose entire body is visible can be seen thrusting his full bodyweight onto the strings; another is gripping a hammer; and yet another is captured halfway through encroaching upon the piano with an unrecognisable instrument. The enchanted faces of the two spectators (a man and woman) support the connotations of a sexual act.

One level of meaning of this image would thus be the dismantling of bourgeois values and sexual morals, without, however, abolishing gender hierarchy. The spectators’ enchanted faces bestow upon events the aura of excitement and fascination.

Dick Higgins commented on one of the pieces performed on that particular weekend as follows:

‘By working with butter and eggs for a while so as to make an inedible waste instead of an omelette. I felt that was what Wiesbaden needed.’[21] The latter remark certainly applied to the entire performance. The festival also provoked comments from the Wiesbaden population in response to the re-education to which they were exposed: this poster was reprinted three years after the event as an instance of self-positioning in Happenings, Fluxus, Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme (eds. Becker and Vostell):[22]

Poster, Wiesbaden Festival of New Music, Scribbles, 1962

As mentioned, the artists organised their own performance opportunities. Below, I will cite from the letters of George Maciunas, which are largely concerned with organisational details, but also have an ideological streak. Astonishingly, Becker and Vostell’s above-mentioned publication already blended a variety of different texts as early as 1965, displaying these without further ado in the art context. Not only reports of the participating artists (predominantly male), but also details of the ‘making of an exhibition’ were included. Disclosing organisational processes implies institutional critique. The conventional notion of a closed, presentable, image-like performance is subverted. ‘Backstage’ affairs are laid bare, thereby dismantling the aura of a work and of the idea of the authentic, spontaneous, and ingenious artist-as-subject.

In 1963, George Maciunas wrote to Joseph Beuys before the latter became a member of the Fluxus movement:

‘To Joseph Beuys, 17 January 1963

Dear Professor Beuys:

I received your letter yesterday evening, and herewith respond to your questions.

- Coming to Düsseldorf already at 10am on 1 February would be somewhat uncomfortable as I would have to stay away from work and would lose 80 Marks. I could come on Friday evening towards 11pm. I must consider the same problem that Emmett Williams has. I will come on 1 February at 10am if it absolutely necessary. Actually Saturday would be enough to prepare things.

- Our manifesto could for instance be a quote from an encyclopaedia (enclosed) on the significance of Fluxus. I enclose a further manifesto.

- We would be delighted if you could perform at the Festival. Wolf Vostell, Dieter Hülsmanns, and Frank Trowbridge will be also taking part as performers and composers. I have revised the programme once more and have included your compositions, although I don’t know which of Trowbridge’s compositions can be performed. I would need to see them before I could agree (…).

- We will not destroy the piano. But can we distemper it (that is, paint it white) and then wash off the paint afterwards?

- My daytime telephone number in Wiesbaden is 54443.

Regards

G. Maciunas.’[23]

This letter, politely phrased and keen to assure Beuys that the piano will suffer no damage, undermines the image of the wild and revolutionary artist-as-subject. Prevailing social conditions, however, become apparent in the avant-garde artist’s addressing Beuys as ‘professor’. The publication conveys the hiatus between revolutionary impetus and polite, bourgeois manners, and makes plain the changing roles of artists, organisers, and collaborators.

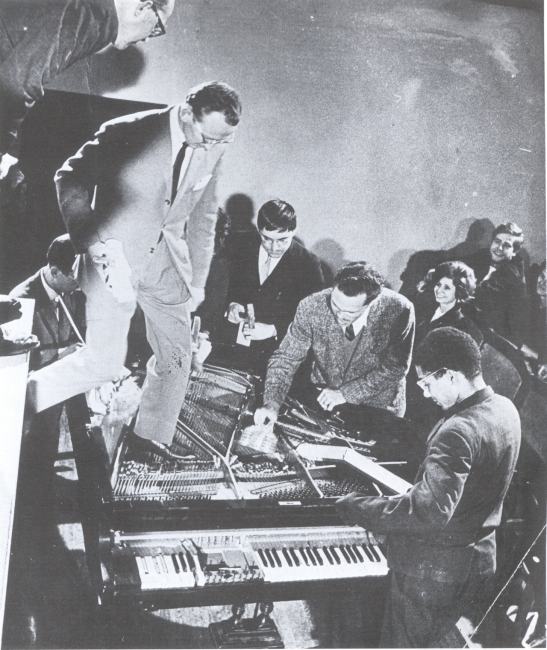

Macinuas’s List of Artists

Maciunas’s self-positioning strategy of compiling lists and graphics that invent and determine the genealogy of the Fluxus movement can be considered both a canonising and hierarchising process and its visualisation. The debates among the artists were first waged in semi-public form in newsletters and subsequently made available to a wider public through the above-mentioned publication. Heated, open-ended debates on in- and exclusion and ideological directions were published.

In retrospect, Maciunas’s role as organiser, arranger, presenter, funds procurer, public relations agent, and namer bears a remarkable resemblance with that of the independent curator, who emerged as a new actor in the cultural field from the 1970s and 80s. In his capacity as Fluxus organiser (and chief ideologist), Maciunas anticipated not only the attribution of creativity, the meaning-giving acts of establishing connections and re-contextualisation, but also the authoritative gesture of inscriptions and exclusions. Also, his attempts to subsume as a meta-artist the works of other artists under a single label (‘Fluxus’) recall the role of a contemporary curator. Just as in today’s independent scene, realising exhibitions and events depends not only on large venues and funds, but also other kinds of desire relations. Personal friendships, networks, group affiliations, and positioning within the field all account for the social capital that allows one to operate in the fine arts. This social network represents social and cultural capital, which can be translated into economic capital. Thus Maciunas’s role transgressed the established roles in the field of art, and anticipated new structures and modes of operation. While the Fluxus images indicate no hierarchical relations among the group of artists, the group is predominantly male. Szeemann’s staging, however, partly adopted and established a hierarchical relation between gestures and stances, suggesting an anarchic, liberated image of the artist, as yet another facet of the myth of the artist.

Third Example: Subject to Negotiation: Curating Degree Zero Archive (CDZA) – an attempt to hold in suspense the relationship between artists and curators

CDZA in Basel, January−February 2003

In 2003, Barnaby Drabble and I initiated CDZA. Together with Annette Schindler, director of plug.in (Basel), we invited curators, artist-curators, and groups of curators from the area of ‘critical curatorial practice’ to take part. CDZA is an archive on the one hand, and a touring exhibition and Web site linked to participant projects on the other. Elektrosmog, the Zürich-based design group, developed a display and navigation system, and Wolfgang Hockenjos designed the CDZA website. In the field of art, archives are practices found increasingly since the 1960s. Hitherto established chiefly by artists and collectors, most recently curators have begun to set up archives to provide access to their collections of material and make public their selection criteria. This result from the dissolution of a self-contained work of art, that is, the disappearance of a contingent art object, which necessitates another form of cultural memory and has always comprised a note of protest and a critique of museum practices. (Fluxus was also predominantly collected in archives, especially the Sohm Archive and the Silvermann Collection). Nevertheless, such archives and the collection and making public of materials tend towards a kind of self-empowerment, aimed at entering cultural memory and to become audible in what Foucault called the ‘murmur of discourse’.

Curating Degree Zero Archive strives towards an open narrative structure, corresponding to the diverse critical contents provided by the participating curators. Arrangement of contents is not unalterable. Instead, CDZA travelled from institution to institution, thus altering and expanding the selection of positions presented in cooperation with the host institutions. We therefore worked closely on content and form with artists, designers, and curators. The basic idea of the archive is progressive and educational, and to gather information otherwise difficult to access into curatorial projects. Via its website, it aims to provide archive users with a navigation structure and to operate as a basis for scientific and applied ‘research’ for both the participating curators and other arts and culture agents. It does not aim to establish a closed narrative, but through a non-uniform range of diverging positions to situate within a framework critical and politically intended curatorial work of individual curators and render discernible contexts. We consider the contradictions arising from the presentation of different practices to be fruitful. We aim to preserve the contradictions, fissures, and divisions and to use the resulting questions as a possibility for obtaining knowledge and insight.

Both Barnaby Drabble and I had until then worked chiefly as curators and authors, but following our commitment we now moved into the position of an artist. Our declared aim, moreover, was to share the power of defining the archive with others in various ways. Thus, the archive is reinterpreted and expanded at each location. We experienced the difficulty of assuming the role of artists towards the host curators when Annette Schindler proposed to display a world map indicating the various exhibition locations. I refuted this idea for various reasons, among others because it would cement a Eurocentric worldview and buttress the conception of the curator-as-author. A standard world map, as a pseudo-egalitarian sign of a television consumer society, would obstruct other views of topography and its national, cultural and geographical meanings. I was unable to assert this position. On the one hand, we programmatically agreed to outsource the power of definition, as described in our concept – while on the other, we found ourselves in a pre-structured, power-shaped institution, which granted us as ‘quasi-artists’ less power than the curator.

The images that we selected to not only document but also represent the archive mostly do not contain this view of the Basel installation. From Basel, the archive subsequently travelled to Geneva, Linz, Bremen, Birmingham, Bristol, Lüneburg, Edinburg, Berlin, Zürich, Mailand, Seoul, Bergen, and Cork.

Let me briefly show you some of the pictures from the different venues.

In line with the title, small panel discussions involving the audience dealt with various issues, for instance how a critical practice could be defined, the relationship between artists and curators, how curating could be taught, and how the relationship with a wider public could be conceived. In order to make the archive productive, debating the archive with local audiences became our central concern.

In some locations, discussions were conducted via Weblogs. Here is an excerpt from our concept, pinpointing questions for discussion:

‘The notion of critical curating in itself already refutes uniformity. It is subject to ongoing historical change, just as the discursive formation of the fine arts is subject to permanent change. In this context, exhibition making is understood as a practice that brings forth, influences, and alters its subject matter. Within the context of Curating Degree Zero Archive, we on the one hand conceive a critical curatorial practice as a content-focused undertaking concerned with political themes, including feminism, urbanism, post-colonialism and a critique of capitalism, and mechanisms of social exclusion. On the other hand, we are interested in structural transgressions of the ”white cube” and classical exhibition formats. Such transgression can refer to interventionist practices, to questioning the art system, and to new forms of transmission as epistemological processes and knowledge production.’

The archive turned itself into a visual manifestation of a discourse about the displaying and mediating of contents. Modes of presentation ranged from funky displays over sculptural forms to discussion form – which raises the key question how materials can be made accessible and curiosity aroused, how they can initiate debates and challenge traditional positions and also the normative effects of displays. Presentations became a balancing act between promising pledges of interaction and amusement for post-Fordist subjects and a realised (not merely symbolic) possibility for debate. For us, the re-interpretation was as good as much possibilities it offered for the public to engage with the material.

CDZA in Berlin

Especially the re-reading of the archive proposed by Lise Nellemann in Berlin provided an opening that made the contours of the groups ‘audience’ and ‘actors’ permeable. Lise Nellemann invited participants, visitors, and artists and curators in transit to present their archive ‘favourites’. Over ten evenings, two or three participants would present their projects for joint discussion. This setting enlarged the group of those mastering the discourse; publications, DVDs, and videos housed in the archive thus became the starting points for the exchange of knowledge and opinion-making. Users thus unfolded the archive’s potential, employing it as a platform for their concerns; our power of definition as initiators and co-deciders on new admissions was also questioned.

Let me return to the world map displayed at the first presentation: within Sasa (44) & MeeNa Park’s reinterpretation of the archive in Seoul in December 2006 and January 2007, the world map prepared by Peters, a Bremen-based scientist, and published by Alfredo Jaar, functioned as a visual node of the discourse. It ended up in the archive as part of the Do All Oceans Have Walls project curated by Eva Schmidt and Horst Griese. This world map was presented differently in that European countries were very small compared to their usual size. It allows us to see how multi-authorial discursive practices in art proceed, namely as a process involving resignification and various authors. Thus, the ‘world map’ was re-performed. Its re-performance clearly revealed that ‘critique’ and signifying processes can be linked and become a joint practice, resulting in an Archive of Shared Interests, as formulated by the De Geuzen artist group.

CDZA in Seoul

Based on the material presented here, one preliminary finding is that artists and curators are involved in a power-shaped constellation. Only through shared content-related interests, political articulation, and joint positioning strategies can concerns be formulated that shift hierarchical arrangements into the background. Artists and curators become collaborators, as evidenced by numerous groups, whose protagonists come from different fields. Curators have quite clearly adapted the procedures of artistic self-organisation and transformed these into hierarchical constructions. However, ‘artists’ and ‘curators’ are no longer functions that can be distinguished in each and every case. Both are involved as cultural producers in signifying processes. Some curators first considered themselves artists (for instance, Ute Meta Bauer and Roger M. Buergel) while in other cases artistic practice contains elements of curating (for instance, Ursula Biemann, Andreas Siekmann, Alice Creischer). Therefore, the term ‘cultural producers’ make sense. Nevertheless, it is imperative that concrete situations are discussed in relation to how power evolves in their cases. This becomes even more necessary, since the nature of art as a commodity suggests an increasingly intense focus on an individual author, thereby misappropriating complex relations and signifying processes.

The possibility of positioning the audience as active participants either in front of a picture as a group receiving instruction or as eye-witnesses or as participants in the picture is fascinating. However, we should not let the matter rest with a promising gesture on the level of a funky display, that is, of participation as a spectacle. The course that power takes must be reversible and authorship must be many-voiced. For us, this meant making available and relinquishing the archive and its interpretation. The archive makes sense for us if it occasions and encourages discussion and processes of self-empowerment, that is, if positions tip over and remain negotiable.

Translated from German to English by Mark Kyburz

Video of the lecture (Videolectures.net)

[1] Beatrice von Bismarck, ‘Curating’, Dumonts Begriffslexikon zur zeitgenössischen Kunst (ed. Hubertus Butin), Cologne, 2002, pp. 56−59.

[2] Cf.: Sören Grammel, Ausstellungsautorenschaft. Die Konstruktion der auktorialen Position des Kurators bei Harald Szeemann, Eine Mikroanalyse, Frankfurt, 2005.

[3] I refer to Wolfgang Kemp’s reception aesthetic approach: cf.: Der Betrachter ist im Bild, Kunstwissenschaft und Rezeptionsästhetik (ed. Wolfgang Kemp), Cologne, 1985; and Wolfgang Kemp, ‘Der rezeptionsästhetische Ansatz’, in: Brassat, Kohle, Methoden-Reader Kunstgeschichte, Texte zur Methodik und Geschichte der Kunstwissenschaft, Cologne, 2003, pp. 107 ff.

[4] See Bismarck, as footnote 1.

[5] Harald Szeemann, 1970, p. 26, quoted in: S. Grammel, see footnote 2.

[6] Robert Smithson, ”Kulturbeschränkung”, Katalog der Documenta 5, Kassel, 1972, quoted in: Kunst/ Theorie im 20. Jahrhundert, Hg. Harrison, Wood, Ostfildern Ruit, 2003, p. 1167.

[7] Szeemann and Bachmann in: Szeemann, quoted in: Sören Grammel, p. 39, see footnote 2.

[8] Daniel Buren, ‘Exposition d’une exposition’, Documenta 5, 1972, quoted in: Oskar Bätschmann, Ausstellungskünstler, Kult und Karriere im modernen Kunstsystem, Cologne, 1997, p. 222.

[9] Walter Grasskamp, Kapitel ‘Kunst der Nation’, Der lange Marsch durch die Illusionen, Über Kunst und Politik, Munich, 1995, pp. 131−153.

[10] Ibid., p. 140.

[11] Walter Grasskamp, ‘Modell documenta oder wie wird Kunstgeschichte gemacht?’, Kunstforum International, Volume 49, 1982 (see Web research KI).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Justin Hoffmann, for instance, subsumes Fluxus, the Viennese Actionists, numerous individual artists, the Situationists, the Affichistes, the Destruction Art Group, the Art Workers’ Coalition, and the Guerilla Art Group under the designation ‘Destruction Art’, which has, however, failed to asserted itself as a term in art history. See: Justin Hofmann, Destruktionskunst, Munich, 1995.

[14] See: Diedrich Diederichsen, ‘Echos von Spielsounds in Headphones. Wie Kunst und Musik einander als Mangelwesen lieben’, Texte zur Kunst, Volume 60, Berlin, 2005.

[15] See: 1962 Wiesbaden Fluxus 1982 (ed. Harlekin Art), Museum Wiesbaden and daad Program, Berlin, 1982, p. 194.

[16] Justin Hoffmann, Destruktionskunst, der Mythos der Zerstörung in der Kunst der frühen sechziger Jahre, Munich, 1995, p. 126.

[17] Sedlmayr was an especially early follower of the Nazi regime, in his post-war lectures his attitude is typical for beneficiaries of the Nazi regime and their line of right wing argument: ‘Above and below are not only spatial relations, but symbols of intellectual ones. (…) It cannot be that one refers to the upper as the lower. You will never call the upper instinctual life and the intellect the lower? This are entirely objective observations. Just don’t feel attacked all the time and constantly take offense! I believe that I take modern art more seriously than all the whitewashers and embellishers who run to its defense. (Applause – stamping and acclamations: Heil Hitler! Acclamation: Pfui!) All I can reply is that I have presented the same matters before and during Hitler, in precisely the same way, with the same avowal of the power of the mind and without the slightest concessions. (Applause).’ Hans Sedlmayr: ‘Über die Gefahren der modernen Kunst’, lectures delivered in 1950, in: Darmstädter Gespräch: Über das Menschenbild in unserer Zeit (ed. Hans Gerhard Evers), Darmstadt, 1959, pp. 48−62, quoted in: Kunst/Theorie im 20. Jahrhundert, Ostfildern-Ruit, 2003 (Oxford and Cambridge, 1992).

[18] See: Silke Wenk, ‘Pygmalions moderne Wahlverwandtschaften. Die Rekonstruktion des Schöpfer-Mythos im nachfaschistischen Deutschland’, Blick-Wechsel, Konstruktion von Männlichkeit und Weiblichkeit in Kunst und Kunstgeschichte (ed. Ines Lindner et al.), Berlin, 1989 and: Barbara Schrödl. Das Bild des Künstlers und seiner Frauen, Marburg, 2004.

[19] Theodor W. Adorno, Gesammelte Schriften, Volume 7: Ästhetische Theorie, 1970, p. 135.

[20] See also: Pierre Bourdieu, Die Regeln der Kunst, Frankfurt a. M., p. 276.

[21] Owen F. Smith, Fluxus: The History of an Attitude, San Diego, 1998, p. 74.

[22] Jürgen Becker and Wolf Vostell, Happenings, Fluxus, Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme, eine Dokumentation, Hamburg, 1965.

[23] George Maciunas in: Jürgen Becker and Wolf Vostell, Happenings, Fluxus, Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme, eine Dokumentation, Hamburg, 1965, p. 197.