Katharina Schlieben and Sønke Gau: Marginalised Artistic Practices and Self-Organisation

World of Art | Year 14 | Reflections and shifts in curatorial, critical and artistic practices

Katharina Schlieben and Sønke Gau: Marginalised Artistic Practices and Self-Organisation: ‘Work to do! Self-Organisation in Precarious Working Conditions’

Thursday, January 26, 2012 at 6 p. m.

SCCA Project room, Metelkova 6, Ljubljana

A crucial question is how to negotiate and to bring into the arena of curating the invisible, the marginalised, the immaterial, or the ephemeral. This question is probably connected to the issue of representation: Who and what is represented in public spheres and how does it come into the fore? How to define the means of representation, how to create and form methodologies of visual translations for ephemeral practices and long-term processes? Probably a detour is necessary: A reflection on institutional framework conditions, namely of conditions under which research-based, participatory, socially-relevant and context-related art production takes place today in connection to funding criteria is of particular importance in relation to the question of representation.

According to the theory of hegemony formulated by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe[1], social regimes and their moral values are formed against the background of permanent conflictive debates played out in the struggle to exert dominance. ‘Antagonisms’ and ‘hegemony’ are the key terms in their concept of radical democracy, which assumes that every regime is pervaded by indecidabilities and constitutive ambivalences, which in turn prevent this very order from totalising itself. Hegemonic practices, striving to assert their order and moral values and establish them as social institutions, are in a state of conflict with counter-hegemonic practices, which for their part attempt to undermine these practices. Thus, even should it succeed in being recognised by the majority as effectively being the ‘natural order’, this dominant order can only ever be precarious and is the expression of what are ultimately temporary power relations. In distinction from a practice of the articulation of politics, which attempts to produce consensus or at least compromises, in her text ‘On the Political’[2] Mouffe sets a concept of the political that starts out from an inherently constitutive antagonistic structure of democracy. In a departure from the belief in the universally valid, reason-based agreement advocated by universalistic theories of the cosmopolitan, her argumentation is thus directed against every form of consensus utopia. She advocates that the fundamental dimension of passionate partisanship needs to be recognised and the representation of the world full of conflicts with opposing camps embraced, as a struggle interest groups fight out to gain hegemony. In line with this approach, social reality is thus configured discursively and identities are always the result of identification processes. The irreducible heterogeneity of antagonisms produces a polyphony that is directed against hegemonic articulation and is hence the essential basis of a public sphere in a political sense.

In his text »’There is a Crack in Everything …’ Public Art als politische Praxis«[3] , drawing on the political theory of Laclau/Mouffe, Oliver Marchart states that to speak of the ‘public’ or ‘public space’ is misleading, for the public is precisely not an a priori given, but must always first be produced, and then each time anew, through conflictual disputes: ‘Where there is conflict, or more precisely antagonism, there is the public, and when it vanishes, so too the public vanishes with it. In this sense the media would not simply be public spheres, but rather the public sphere itself a medium. The public sphere would be the ‘tie of separation’ that connects qua conflict. It is only in the moment when a conflict is played out that a public sphere arises in which different positions clash apart and so come into contact.’[4] In terms of art, it can only be public in a political sense when it takes a standpoint, i.e. ‘when it takes place in public, i.e. in the medium of the antagonism.’[5] This occurs by ‘marking a counter-position as a component in a broader attempt to create counter-hegemony.’[6]

In the context of the hegemony theory of Laclau/Mouffe and Marchart’s explications on pubic art as political practice, it makes sense to counter the currently dominant ascription of value to art indulged in by most founding institutions and a large section of the art market with models of self-organisation which enable a different artistic practice. These artistic practices often attempt to engage in a different form of knowledge production and publication. In many cases they are part of heterogeneous networks which temporarily combine their polyphonic standpoints so as to be able to produce larger sub-publics for their concerns.

But these artistic practices generate very different challenges than that of producing artworks in the sense of a sellable product preferred by the art market and many founding institutions. The effort needed for their realisation, covering research, production, distribution and reception, thus also raise fundamental questions on the possibilities of curatorial practice. The following considerations reflect these issues as they emerged in some of the approaches taken in the project series Work to do! Self-organisation in Precarious Working Conditions[7], curated by us and held at the Shedhalle in Zürich between 2007–2009. Further, these will be followed in turn by some thoughts in relation to the paradoxes of the funding situation, which we once formulated as ‘Caught between two stools’[8]

Gathering formats

The project series Work to do! Self-Organisation in Precarious Working Conditions examined the dynamics, emancipatory movements, and self-empowerment potentials as well as the paradoxes and problems of self-organisation concepts in times of huge transformations of working conditions in our society. In this series communication between contexts and different logics of knowledge became a challenge in terms of what self-organisation could mean beyond the art context and what learning-from-others and self-education means in its consequences. Communicative processes in relation to self-organisation are of fundamental importance for both the internal organisation amongst the involved subjects as well as presenting their respective concerns externally and generating publics and or sub-publics. The project series Work to do! took these considerations as one of its starting points to reflect on and to link to communicative necessities, possibilities of collective knowledge production, interactive communication, and mediation in self-organised contexts.

If knowledge production and mediation/communication practice is not thought as categorically separate, then, along with the questions, how is knowledge produced and who communicates with whom and why, who speaks for whom, the issue of their relationship to one another emerges. Our interest was to find out how these two areas could overlap and to focus on the in-between as a productive possibility. The perspective and logic of Work to do! was to bring together actors and interested parties from the respective knowledge fields in a dialogue which attempts to grasp expert, interested and practice knowledge as levels with equal status and understands the roles in connection with collective knowledge production as exchangeable. For the three project parts we proposed three different dialogue formats: Meetings with Initiatives, Dialogical Talk Series, and Skype Meetings.

To become acquainted with self-organised initiatives in Zürich and to find out more about them, a series of meetings were held with such groups during spring 2007. We wanted to get to know the people and places behind these initiatives and learn about their motivations, working conditions, structural organisation, economic basis, and visions. The spectrum ranged from initiatives, which can already look back on a certain tradition, to others in the process of being formed and trying out new forms of organisation and articulation.

Both project participants as well as Shedhalle visitors were invited to the Meetings with Initiatives. These interactive visits were understood as a kind of public research featuring direct exchange and talks; the primary goal was to identify and discuss those questions which in turn went on to decisively influence the conception and line of questioning of the overall project series. These discussions with protagonists from the initiatives and project participants were documented and subsequently integrated into the exhibition. Leaving behind the institution of the Shedhalle – and thus our own context – and going to the locations where the initiatives work, provided all participants with the opportunity to get to know these structures. For us, it was important that Shedhalle visitors were not excluded from the research, and so we sought to consciously conceive a framework in which questions could be developed jointly or carried forward. At the same time, proposals and criticism from the initiatives concerning the project series or individual project conceptions became components of the further development.

Beside the gathering formats, seven artistic projects of the series developed over time in the sense of ‘The menatal comma instead of the Full-Stop’[9]. Two projects will be described more in detail:

1.

A) Building Material Centre – A compilation of Zürich resources, sighted and secured by Folke Köbberling and Martin Kaltwasser for a downtown Satellite of the Shedhalle, Shedhalle, spring 2007.

B) Werdplatzpalais, Werdplatz/Zürich, autumn−winter 2007.

C) Filiale Micafil, Altstetten, since summer 2008.

The artists Folke Köbberling and Martin Kaltwasser and the curators collected and sorted valueless materials for the Building Material Centre at the Shedhalle before they were then used for constructing a satellite in the city centre of Zürich. Visualizing the materials as well as the stories and places associated with them, which provided insight into the concrete situation in the city, was central. The collected discarded and unwanted materials throughout the entire Zurich urban area was first sorted and stacked and put on show in the 18 shelves of the Building Material Centre. During autumn/winter 2007, in the form of a pavilion (a Shedhalle satellite), the Werdplatzpalais, located on Zürich’s Werdplatz, was build out of the collected material for the next step. The form and location of the satellite referred to its surrounds by accompanying the existing footways and providing sitting areas. The satellite, used for film screenings and talks, reformed the square on all sides, forming a temporary centre point open to all members of the public and to self-organised initiatives, which have no office or meeting point. The satellite was made up of four shelf modules, coming from the Building Material Centre, out of which a central interior space was formed. During spring/summer 2008, the material re-entered the public realm for a third time. The community centre Loogarten in Altstetten asked the artists to build another house with and for children. Working together with kids and youths from the Loogarten community centre, the artists built the offshoot Filiale Micafil as a meeting place in the Micafil residential settlement in the Zürich suburb of Altstetten.

The collection of materials to be recycled at the Building Material Centre in the Shedhalle – which for months acted as a storehouse, production, and exhibition site in one – and later erected in the form of the Werdplatzpalais, a temporary meeting and discussion place and later as the Filiale Micafil, revealed a cycle of re-deployable materials that the citizens of Zürich had thrown away and thus defined as valueless. The project addressed three different publics and defined three spatial figures of gathering. The first step – and its practice knowledge – was necessary to get to the second and further the second to get to the third.

Central for the other project, we would like to describe, was as well not to illustrate self-organisation, but to find out how self-organisation could come about.

2.

1 CHF = 1 VOICE is a political art intervention (summer 2007−summer 2009), initiated by Andreja Kulunčić. The project could be understood as a thing as a moment of gathering in which elements publicly correlate, complement each other, and offer new scope for action. One starting point was to involve a plurality and polyphony of heterogeneous parties, which look for emancipation, antagonism, and self-criticism within migrant political activities.

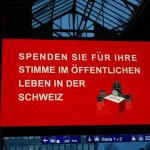

Briefly in advance: the idea of the action itself was to give invisible, illegalised people a public voice. The action wanted to make available a tool for illegalised persons/Sans-Papiers in Switzerland (activists estimate that about 300,000 undocumented immigrants are living in a precarious situation in Switzerland, the ‘official’ number is 80,000) through which they can attain visibility on the political and public level. The concept as well as the action was developed with and for Sans-Papiers. The idea of the campaign was that Sans-Papiers were invited to anonymously donate one Swiss Franc through the account of SPAZ (Centre for Sans-Papiers in Zürich) for the renovation of the Swiss Parliament, which was under renovation until 2009. The Parliament is usually considered as the public voice of every country, and in addressing it, the idea was to address the requests of Sans Papiers to Swiss society. Through the act of donation to society, the Sans-Papiers sent a message that they want to take part in carrying out obligations, but also in having privileges in the society in which they are living and working. The handover of the raised money to the parliament, Switzerland’s representative and most democratic building and thus for Swiss society, is to be understood as gestures of approaching others, of seeking contact and entering a dialogue. The financial aid should guarantee a long-term symbolic visible presence in/on the federal parliament, reminding the parliamentarians (through a plate saying ‘Donated by Sans Papiers for the renovation of the Parliament’) every single day of the need to take political action and challenging them to finally recognise how Sans-Papiers contribute to society. The action aims at giving Sans-Papiers a voice and making the invisible visible. Since summer 2007, the project campaign has been translated into many languages by various migrant initiatives and has been circulated in the Swiss press, free magazines, and Zürich public domains, for example through an eBoard clip at the main railway station, the project website, notices, advertising spots in cinemas, and newspaper articles. Furthermore, a video was produced for and about the project that illuminated the campaign from a variety of perspectives. Voices from Sans-Papiers, political initiatives, politicians, the artist and the curatorial team on perceptions and perspectives of the project were gathered together in a series of interviews. For more than a year the Shedhalle office acted as a kind of networking, communication, and distribution headquarters.

The project wanted to initiate different dialogues between different parties, which are not necessarily separated: the illegalized people, the art context, the activists and the parliamentarians. The challenge was to shift one’s own position into a dialogue.

Questioning Production Conditions …

In terms of both their content as well as selected methodologies and performance, the projects of the series Work to do! were experiments in identifying and fostering alternative dynamics and economies of social exchange, and wished an sustainable impact on public spheres and precisely on their partly unexpressed conflictual marginal spaces. The concept of what constitutes an artwork developed here into a notion of practice that incorporates pre- and post-production as well as reflective mediating tools and in turn entailed their archiving and distribution.

We described the funding situation and production conditions of such kind of projects like 1 CHF = 1 VOICE or Building Material Centre as ‘Caught between two Stools’[10]: Whilst the art market booms and a selected few artists manage to make money through their involvement in the market, it seems as if such kind of practices and the institutions making the effort to support them remain ‘caught between two stools’, and indeed that the space between these stools is becoming increasingly restrictive. In many cases we have described ‘in-between space’ as productive and still understand it in the sense of the non-categorisable, permitting the emergence of other spaces for thought and action. In the case of financing such projects however, we have experienced how the attempt to critically question the neo-liberal exploitative absorption of moments of self-organisation has, given Shedhalles framework conditions, unfortunately also led to a re-production of precarious working conditions. ‘Mental Comma instead of the Full-Stop’ − approach of the project series did result in ‘More Work to do!’ for all involved. We consider it necessary to think about approaches towards funding culture which are neither work − nor category-oriented and do not exclude immaterial, temporary, intervention project formats. While applying for financial support for artistic projects in the Work to do! project series, it soon emerged that many foundations are fully unprepared for this kind of art production or have little knowledge about the funding necessities. Narrow definitions of what constitutes a work, inflexible funding categories and fixed cycles, categorically presupposed for artistic production, inform and rigidify the selection criteria for funding projects and thus indirectly also the possibility of their realisation and public visibility.

It is not possible to think about art practices without discussing their production conditions and the various parties involved in that process. Such a focus demands from art institutions and those institutions contributing to art and culture funding an analysis of artistic working and production conditions and their methodologies, while also simultaneously self-reflectively experimenting with strategies and instruments, so as to pose productive questions as to find possibilities of implementing and financing such practices. The aforementioned projects received financial support amounting to some 10 % of their actual costs through the Shedhalle and other funding institutions; the remaining 90 % was covered by voluntary work and various contributions from individuals and groups who share the same concerns and wished to express their solidarity. This amount does not appear in the project budgets. The ‘more’ work we mentioned also refers ultimately to financing and commitment, and is very difficult to quantify in its full dimensions.

We assume that many project initiatives and institutions have gathered their own experience in these issues, both similar and different to ours, and we consider it imperative to address anew the following issues in relation to funding criteria:

- Fee policy for artists.

- Redefining production procedures, including pre- and post-production as well as mediating and distributing tools.

- An Understanding of various kinds of project dynamics that allow for long-term projects.

- Support of collective working practices.

- Support of transdisciplinary approaches.

- Financing research in early stages.

- Creating possibilities of transnational collaboration and exchange.

- Acknowledging discursive programmes as being an integral part of the knowledge production and the project itself.

Video of the lecture (Videolectures.net)

[1] Ernesto Laclau/Chantal Mouffe, Hegemonie und radikale Demokratie. Zur Dekonstruktion des Marxismus, Wien, 1998 / Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. Towards Radical Democratic Politics, New York, 1985.

[2] Chantal Mouffe, Über das Politische. Wider die kosmopolitische Illusion, Frankfurt am Main, 2007 / On the Political., New York, 2005.

[3] Oliver Marchart, »’There is a crack in everything …’ Public Art als politische Praxis«, in: Kunst und Öffentlichkeit. Kritische Praxis der Kunst im Stadtraum Zürich (eds. Christoph Schenker, Michael Hiltbrunner), Zürich, 2007, p. 236–244. Cf. the more detailed text by Oliver Marchart, Art, Space and the Public Sphere(s). Some basic observations on the difficult relations of public art, urbanism and political theory at http://www.eipcp.net/transversal/0102/marchart/de.

[4] Ibid. 239−240.

[5] Ibid. 241.

[6] Ibid. 243.

[7] Gau/Schlieben, Work to do! Self-Organisation in Precarious Working Conditions, Nüremberg, 2009.

[8] Gau/Schlieben, Caught Between Two Stools – or on the necessity of considering new approaches to funding culture, in: Ibid.

[9] A curatorial metaphor expresed by Johanna Lassenius and title oft he Editorial of the Newspaper Shedhalle, No. 1, 2004.

[10] Gau/Schlieben, ‘Caught Between Two Stools’ – or on the necessity of considering new approaches to funding culture, in: Work to do! Self-Organisation in Precarious Working Conditions, Nüremberg, 2009, pp. 218−236.