Survey lecture derived from Retort talk, May 2004

Julian Stallabrass

Predavanje, 15. november 2007 ob 19.00

Projektna soba SCCA, Metelkova 6, Ljubljana

At first sight there seems to be no system against which art is currently more differentiated than the global neoliberal economy, founded on the ideal if not the practice of free trade. The economy functions strictly and instrumentally according to iron conventions, imposed unequally on nations by the great transnational economic bodies (the World Bank, the World Trade Organisation and so on); it establishes hierarchies of wealth and power; it enforces on the vast majority of the world’s inhabitants a timetabled, and mechanical working life, while consoling them visions of cinematic lives given meaning through adventure and coherent narrative (in which heroes make their lives free precisely by breaking the rules), and with plaintive songs of rebellion or love. This is the nerve pressed on by Johnathan Richman’s deceptively saccharine song, ‘Government Center’. Here are some of the lyrics:

We gotta rock at the Government Center

to make the secretaries feel better

when they put the stamps on the letter…

The song ends with the dinging of a typewriter bell. It tells its listeners what pop songs are (mostly) for.

Art appears to stand outside this realm of rigid instrumentality, bureaucratised life and its complementary culture. That it can do so is largely due to art’s peculiar economy, founded in the manufacture of unique or rare artefacts, and on its resistance to mechanical reproduction.1 That resistance can be seen most clearly in the tactics used by artists and dealers to constrain artificially the production of works made in reproducible media, with limited edition books, photographs, videos or CDs. [Eyestorm’s Barney soundtrack; ed. of 700, $90; that Barney’s work also now sold in ordinary stores may be beginnings of breakdown, as we shall see; Christian Jankowski’s gallery-sold videos to viewers, in a large edition of 500 for £200 each; and museum quality DVDs with licence to show publicly for £10k; for Point of Sale a management consultant interviews an art dealer and an electronics dealer about their businesses, each giving the others’ answers—point being about the distinctiveness or otherwise of the art business]

The art market is regulated by dealers who control not only production but also consumption, vetting the suitability of buyers for particular works; the ‘who are you?’ question to buyers. There is less regulation in the so-called ‘secondary market’ of the auction houses, but even there the market is hardly free, being subject (aside from the recent scandals about systematic price-fixing) to reserve prices below which a work will not sell, and the manipulation of prices by owners buying up their own pieces. This small world (which from the inside can appear autonomous, a micro-economy in which market feedback is produced by a few important collectors, dealers, critics and curators) produces art’s freedom from the market for mass culture. To state the obvious, Bill Viola’s video pieces are not play-tested against audiences in the Mid-West, nor are producers forced on art bands like Owada to ensure that their sound will play inoffensively in shops. So this cultural enclave is protected from vulgar commercial pressures, permitting free play with materials and symbols, along with what has become the standardised breaking of convention and taboo.

The freedom of art is more than an ideal. If, despite its great insecurity, the profession of artist is so popular, it is because it offers the prospect of unalienated labour in which artists, unchained from the division of labour, and like heroes in the movies, endow work and life with their own meanings. Equally for the viewers of art, there is the possibility of a concomitant freedom in appreciating the purposeless play of ideas and forms, not in slavishly attempting to divine artists’ intentions, but in allowing the work to elicit thoughts and sensations that connect with their own experiences. The wealthy buy themselves participation in this free zone through ownership and patronage, in part because such participation is a genuinely valued good; the state ensures that a wider public has at least the opportunity to breathe for a while the scent of freedom that works of art emit.

Yet there are reasons for wondering whether free trade and free art are as antithetical as they seem. To begin with, the economy of art does closely reflect the economy of finance capital, if not capital as a whole. In a recent analysis of the meaning of cultural hegemony, Donald Sassoon explored patterns of import and export of novels, opera and film in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Culturally dominant states have abundant local production that meets the demands of the home market, alongside much exporting of cultural goods and few imports.2 In this way, France and Britain were dominant in the production of literature in the nineteenth century. Currently, for mass cultural products, it is clear that the US is by far the dominant state, exporting its products globally while importing very little. As Sassoon points out, this does not mean that everyone consumes American culture, just that most of the culture that circulates across national boundaries is American.3

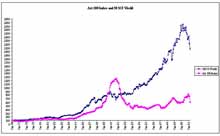

Sassoon rules fine art out of his account on the sensible grounds that it has no mass market. Trade figures are in any case hard to interpret in a system that is thoroughly cosmopolitan, so that you may have a German collector buying through a British dealer the work of a Chinese artist resident in the US. We can, however, get an idea of the volume of trade in each nation, and, given the high volume of international trade in the art market, this does give an indication of global hegemony. Here there are striking parallels with the distribution of financial power. As one might expect, the US is dominant, accounting for a little less than a half of all global art sales; Europe accounts for the great majority of the rest, with the UK taking as its share around a half of that. France is a major source for art-dealing, while Italy and Germany also have significant markets.4 Art prices and the volume of art sales tend closely to match the stock markets, and it is no accident that the world’s major financial centres are also the principal centres for the sale of art. To raise this parallel is to see art, not only as a zone of purposeless free play, but as a minor speculative market in which art objects are used for a variety of instrumental purposes, including investment and tax avoidance.

(MSCI leader in equity tracking; Example of instrumental uses of art; Japan before the recession; and property scam; the divergence of art and stocks.) [graph] Scam in Japan in which works of art were used to launder huge slush funds to benefit corrupt politicians and organised crime: government curbs on profiting from real estate were stepped around by sellers ‘buying’ a painting on the understanding that it would soon be bought back from them at perhaps ten times the original price. The damaging thing here was not merely that secret deals were being made or tax avoided—standard characteristics of the Japanese art market—but that the scam distorted the market. Suddenly it seemed that the Japanese penchant for paying large amounts of money for undistinguished Impressionist and post-Impressionist paintings was less a matter of naiveté than unscrupulous calculation.

Two main features of 1990s art may at first sight seem to cut against this picture. If the US is so dominant, how is it that contemporary art is made and exhibited all over the globe, particularly in the rise of the global biennales? And if the market is so important, why the renewed rise of installation art, which at least in its origins resisted saleability?

- Rise of Biennales

Havana Biennial (1984), Sharjah Biennial, United Arab Emirates (1993), Gwangju, South Korea (1995), Johannesburg Biennale (1995-97), Shanghai Biennale (founded 1996, opened to international artists in 2000), Mercosur Biennial held at Porto Alegre, Brazil (1997), DAK’ART, Senegal (1998), Busan Biennale, Korea (1998), Berlin Biennale (1998), and the Yokohama Triennale (2001), Prague (2003). - Hybridity etc. & the virtuous cultural mixing that results from these engagements; of international stars and the local art scene, encouraging the rise of new voices, and supposedly undermining the old hierarchies of the nation state.

- Global competition, especially between cities

The biennale has two main benefits that mark it out from a fair of new technology or an important football match. Firstly, despite all the academic nay-saying from critics and theorists, art retains in the public and civic eye a kudos that transcends ordinary culture and entertainment, and gestures towards the universal. As such, it performs the same function for a city—with all its crude jostling for position in the global market—as a Picasso above the fireplace does for a tobacco executive. Secondly, it not only embodies but actively propagandises the virtues of globalisation. There is a contradiction here, which I will just touch on for the moment: if applied to art itself the stringent demands of globalisation and its economic order would destroy the very thing that art is valued for (and with increasing state and corporate demands, that is a very real threat).

- Limits in eg Havana and Johannesburg, where the main audience catered to was plainly the international art elite, not the locals; Sierra’s SS Invites You for a Drink; the related work shown at PS1, where worker was hired for this continuous period of 15 days and nights to inhabit a space walled off from the gallery goers.

- Kind of art that tends to flourish here; splicing of local concerns/ material with elements of post-conceptualism; and often that those local concerns be at the forefront of media attention.

- Connected is rise of genuinely radical political content—Documenta 11 here being a recent exemplar; if it remains in art enclave, then necessarily supplementary, ineffective, and in bad faith (Collings/ Arnatt line); but that containment increasingly difficult.

The other main feature: rise of installation art, after a long hibernation through the 1980s. Installation has two marked advantages. The first is in the continuing competition with mass culture—how to persuade an audience to travel to a museum or other site rather than watch television, go to the movies, a gig or a football match, or shopping. There has been an intensification of competition here, a vying for spectacle, with television to take one example, transforming itself with large, wide screens, high definition and DVD recording as the museums continue their own commercialisation. In part, as we have seen, art sets itself off from mass culture by its handling of content. Aside from that, what the reproducible media cannot simulate is the feeling of a body moving through space surrounded by huge video projections or work that has weight, fragrance, vibration, or temperature. Installation, that allows a space to be inhabited, rather than merely presenting an art work to be looked at, thus comes to the fore. In this battle over spectacular display, artists and museums have avidly seized on new technology, especially digital video and video projection. [Expense of these projects, e.g. Mori, whose piece was custom-built in a car factory.]

Second, the commissioning of a work for a particular site that will only be seen in that location is a way of ensuring that viewers have to go there, and collections of such works by important artists clustered in a Biennale form powerful magnets for art-world attention. E.g. Salcedo at Liverpool. In this way, installation and site-specificity are linked to the globalisation of the art world, and an art used for regional or urban development. Given that this is now the regular strategy, the necessity of being there has become another way to confirm social distinction on the viewer (as only slight exposure to art-world chatter, so often fluttering about the latest exotic jamboree, will confirm).

Links between installation and other elements in 1990s art: the US culture wars may be seen as a domestic prelude to the wider issues of global hybridity, and were constituted by the same disposition of forces: on one side, liberal consumerism committed to the demolition of restraints on commerce in the broadest sense, and on the other the local forces of tradition, religion, and moral deportment. Installation (again, broadly taken) is associated with spectacle and competition with the mass media. Contemporary installation is expensive and is generally reliant on private or public funding. It is thus tied to corporate involvement in the arts and the commercialisation of the museum, in a way that directly cuts against its origins in do-it-yourself artists’ projects; this in turn is linked to the connection between globalisation and privatisation (of which the privatisation of the art world is just a small part) which pressures the art world into ever more spectacular display. Similarly, the symbiosis with elite elements of mass culture, and the urge to engage with ‘real life’ (which is to say, consumer culture) are part of the same impetus. [tillmans]

Back to basic structure of art as protected realm between instrumental life and mass culture. It must continually display the signs of its freedom and distinction from the mass, by marking off its productions from those of cultural products bent to the vulgar forces of mass production and mass appeal. It often makes a virtue of obscurity or even boredom to the point that these become conventions in themselves. [Stan Douglas] Its lack of sentimentality is a negative image of the sweet fantasies and happy endings peddled in cinema and television. [Libera x3] In its dark explorations of the human psyche, of which the worst is almost always assumed, it appears to hold out no consolation. Yet, naturally, all of this ends up being somewhat consoling, for its over-arching message is that such a zone of freedom can be maintained by the instrumental system of capitalism.

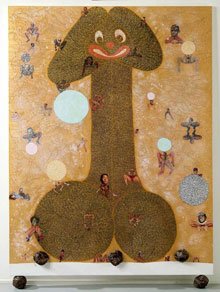

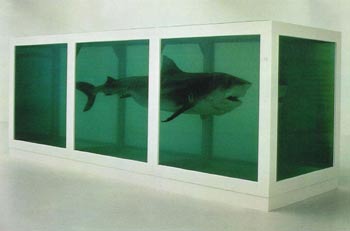

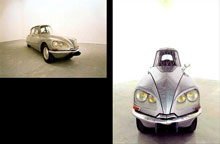

However, and most dangerously for the ideal of unpolluted cultural freedom, it is possible to see free trade and free art not as opposing terms but rather as forming respectively a dominant practice and its supplement (a dependent but necessary addendum to the main track of the world economy). So the tireless shuffling and combining of tokens in contemporary art in its quest for novelty and provocation (to take some well-known examples, sharks and vitrines, paint and dung, convincing simulacra at odd scales, slimmed down cars) closely reflect the arresting combinations of elements in advertising, and the two feed off each other incessantly. As in the parade of products in mass culture, forms and signs are mixed and matched, as if every element of the culture was a fungible token, as tradeable as a dollar. Furthermore, the daring novelty of free art, and its continual breaking with convention (at least, so curators assure us) is but a pale rendition of the continual evaporation of certainties brought about by capitalism itself.

The supplementary character of free art to free trade is becoming more visible as both corporations and states, aware of the lack in free trade, attempt to supplement it by making instrumental demands on art. Corporate demands on art have become more widespread and systematic. Business enters partnerships with museums or artists in which the brand of one is linked with the brand of the other in an attempt to inflate them both. [b&q] Strict criteria are followed in deciding whether to support art events or institutions.5 Among the most important of these are whether the art audience matches the business’ target markets, the likelihood of extensive media coverage and the promotional potential of the artists involved. Among the systematic effects that corporate decision-making has had on the arts are the emphasis on the image of youth (an attempt to capture youthful, sophisticated but jaded consumers long inured to the effects of advertising), [Peyton] the prevalence of work that reproduces well on magazine pages, and the rise of the celebrity artist. [Sam T-W and Elton] Corporate curating etc. [siemens, art and economy] in which businesses directly set cultural agendas.

Aside from these immediately commercial concerns, corporations have been involving themselves in programmes that widen access to the arts, or link it to progressive social causes. Their involvement in such causes produces a double effect: to draw in a diverse or disadvantaged audience, partly in the hope that upward mobility may produce future consumers, and mostly to assure the elite audience for art that what they are seeing are not merely aesthetic sweeties (the consumption of which is haunted by guilt) but also phenomena of worthy social significance.

Recent state demands on art complement those of the corporations, for both have similar interests in fostering social calm, cohesion and deference in the face of the gale of creative destruction that the economic system they are committed to propagating continually gives rise. In Britain, the Labour government saw art as a way to boost the economy, particularly in the so-called ‘creative industries’, as a tool to regional development, and as a social balm to heal the divisive social rifts opened up by the long years of Conservative rule.6 Art should be of ‘quality’ without being elitist, and should draw in new, diverse audiences. There are similar moves in the US where National Endowment for the Arts funding, long under successful attack from conservative politicians, is justified on the grounds that art has a role to play in social programmes, including crime reduction, housing and schooling. The danger of such moves—highlighted in a survey of attitudes entitled Art for All in which there is much moaning about state direction of the arts—is that in revealing the instrumentality of art, they also reveal with too much clarity the relationship between art and the state, which is most useful, after all, if it is thought to be founded on idealism and eternal human values.7 Art can only meet the instrumental demands of business and state if its function is concealed by the ideal of freedom, and its qualitative separation from free trade is held to faithfully.

Contemporary global art pushes against the borders of local particularity, and aids the transformation and mixing of the world’s cultures and economies. The progressive and regressive aspects of this process are inextricably related. Local resistances are defeated, and in many places local conditions worsen as a result. Equally, it prepares the way for greater integration, for the evolution of wider solidarities and actions, which have indeed been emerging. Again, though, any progressive aspect to the art world’s support of neoliberalism is again the inverse of its view of its actions, which are fixed on the particular, the personal and the non-instrumental. It is just this mismatch that constitutes art’s main contribution to what is, after all, far more effectively carried on by mass culture: an appeal to sections of the elite that stand above and aside from their local cultures and a particularly effective ideological cloak for the actions of that audience in their engagement with global capital.

There are, however, distinct tensions and contradictions in this situation. We have seen that art’s uselessness–its main use–is being sullied by the particular needs of government and business. [an extreme example is art playing with and progandising/ glamorising genetic manipulation] In a linked development, art’s elitism is challenged by the attempt to widen its appeal; business values art for its socially elite character while states are generally interested in widening its ambit, and thus undermining its exclusive character. Finally art’s means of production, increasingly technological, has come into conflict with it archaic relations of production.

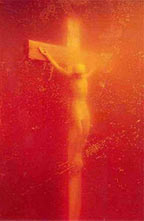

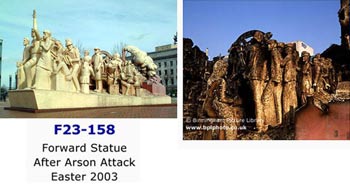

Opportunities for the exploitation of these tensions fall into four main categories. First, there is iconoclasm. The destruction of art, or even the attempt to do, is the most basic protest against the notion implicit in contemporary art that all signs are equally open to play (the relatives of Myra Hindley’s victims thought that her image should not be open to such toying with, and were supported by two people who tried to damage Marcus Harvey’s Myra [myra] on display at the Sensation exhibition; likewise Chris Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary, which juxtaposed the main figure with cut-outs from pornographic magazines, was attacked when Sensation was shown in New York). Such acts also challenge the commonly held view that all art is a good, a product of sovereign self-expression, and in attacking public works, it places attention on art’s setting and use. The destruction of municipal contemporary sculpture, such as the well-planned arson attack (2003) in Birmingham on Raymond Mason’s Forward (1991), [slide] much disliked by many locals, raises just these questions.

The second is outright political activism in art, e.g. Salgado’s work for the MST; and the third the often linked exploitation of technological means to sidestep the art world system. Involving the dematerialisation of the art work in data, which can sidestep many of the factors governing the mainstream art world: ownership, curating, state and corporate demands. Most of all, it can offer art a use.

The question of art’s use takes us back, naturally, to art’s freedom. That the very concerns of art—creativity, enlightenment, criticality, self-criticism—are as instrumentally grounded as what they serve to conceal—business, state triage and war—is the consideration that must be concealed (and can be, because local liberation offered in the production of art and its enjoyment are genuine). Art celebrates as freedom all that is forced upon us. In The Rules of Art Bourdieu cites a letter of Flaubert’s on art’s freedom:

That is why I love Art. There, at least, everything is freedom, in this world of fictions. There one is satisfied, does everything, is both a king and his subjects, active and passive, victim and priest. No limits; humanity is for you a puppet with bells you make ring at the end of his sentence like a buffoon with a kick.

Flaubert more than implies that the free mastery of the artist (and reader or viewer) is a cruel power. In Bourdieu’s analysis, Flaubert’s freedom, and that of the avant-garde in general, was purchased at the price of actual disconnection from the world of the economy: other bohemian writers were the main and grossly inadequate market for such work, books were written in deliberate defiance of bourgeois understanding; the autonomy of art was carved out of a reaction against both elevated bourgeois writing and engaged, realist literature; success, if it came at all, was only achieved after the long passage of time, as new avant-garde forms displace and familiarise the old. It is easy to see that the conditions for that freedom no longer exist in the art world: artists are snug in the market’s lap; works are made to court the public; sufficient autonomy is maintained to identify art as art but otherwise most styles and subject matter are indulged in; success generally comes swiftly, or not at all.

In these circumstances, the plausibility and power of art’s freedom are waning. Among the opening remarks of Aesthetic Theory, Adorno has this to say about artistic freedom: ‘…absolute freedom in art, always limited to a particular, comes into contradiction with the perennial unfreedom of the whole.’ Until that wider unfreedom is effaced, the particular freedoms of art run through the fingers like sand. While they may open a utopian window on a less instrumental world, they also serve as effective pretexts for oppression. To break with the supplemental autonomy of free art is to remove one of the masks of free trade. Or to put it the other way around, if free trade is to be abandoned as a model for global development, so also must be its supplement, free art.

1 The point is sharply made in Eric Hobsbawm’s lecture published as Behind the Times: The Decline and Fall of the Twentieth-Century Avant-Gardes, Thames and Hudson, London 1998.

2 Donald Sassoon, ‘On Cultural Markets’, New Left Review, new series, no. 17, September/ October 2002, pp. 113-26.

3 Ibid., 124.

4 The Art Sales Index figures for 2000-01 of percentages of the overall market are: USA 48.9, UK 29.29, France 6.27, Italy 2.9, Germany 2.79. See www.art-sales-index.com

5 See Mark W. Rectanus, Culture Incorporated: Museums, Artists and Corporate Sponsorships, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2002, p. 30.

6 See Chris Smith, Creative Britain, Faber and Faber, London 1998.

7 Mark Wallinger/ Mary Warnock, eds., Art for All? Their Policies and our Culture, Peer, London 2000.