by Sandra Belšak

Pretty Dirty was the concluding exhibition of the 2004/2005 Course for curators, which was on view from 24 June to 22 July 2005 in Škuc Gallery in Ljubljana. SCCA, Center for Contemporary Arts − Ljubljana has been organising the World of Art, School for Contemporary Art for the past eight years. The course is the school’s basic part and the concluding exhibition presents their work guided by the mentors Nevenka Šivavec, the curator at the Likovni salon Gallery in Celje, and Alen Ožbolt, visual artist and writer.

The curators of the exhibition – Ivana Bago, student of art history and English from Zagreb, Miha Colner, final year student of history of art, Ida Hiršenfelder, final year student of Chinese studies, Monika Ivančič, graduate in history of art and sociology of culture, Nina Kodrič, final year student of cultural studies, Mojca Manček, graduate in cultural studies, and Tanja Pavlič, student of history of art – selected as the premise for developing the concept of the exhibition the phenomenon of personal hygiene. After ten months of work, coordinating and reaching consensus and compromise, the extensive exhibition of works by Slovenian visual artists was prepared (they were limited to selecting works dated between 1995 and 2005). “We wash our hands, wash our brains, clean our tongues, erase memories, and disinfect ourselves and our environment. Cleanliness and dirt are associated with beauty and disease, the body and the environment, micro and macro hygiene. (…) A large part of a person’s everyday life and philosophical contemplation is occupied by this subject,” the curators wrote in the text accompanying the exhibition.

Young curators were limited by the venue and budget, and also had quite a few difficulties coordinating and compromising, as a group of seven different views had to work together as “a single curator”. At the end, they all admitted that group work was more difficult than they had imagined, adding that they had gained immense invaluable experience by working in the group, which will benefit them in their future careers as curators.

The installation of the exhibition is pretty clean, clear and logical. The catalogue/accompanying publication is also an art object, printed on waste paper due to lack of funding, cut and collated manually without binding or gluing. If they had run out of money for a “pretty” catalogue, waste paper, already printed on, seemed like a good idea, but they did not go all the way, as the catalogue is not completely different from usual ones printed on clean paper. Perhaps the curators could leave it to the visitors to assemble what they wished from the (original) poster form and would, for example, write only instructions (which would neatly complement the instructions for making tea on the previously printed side of the “catalogue”).

Pretty Dirty, the telling title of the exhibition, can be read in at least two ways: as opposing concepts of prettiness (cleanliness) and dirt, or as being clean/totally dirty. The first example is a necessary opposition, as there is no cleanliness without dirt, which would not be perceived without its counterpart. There is a neutral, golden mean between clean and dirty: just the right amount of clean or dirty, but this is never constructive for artists.

The other way of reading the title as clean/totally dirty could refer to the issues raised in the catalogue by the curator Mojca Manček when she observes that, by obtaining funding, the curator “enters the area of the art market, where there are certain governing principles, asking oneself what is clean and what dirty in this respect”. This is an interesting problem, which could be the subject of wide debate among artists and curators. Wherever there is money, there is also the “dirt” of human greed, of the struggle for privileges. A question of morality, which is part of a person’s mental hygiene, and where there are also essential minimum standards of hygiene.

In the introduction to the catalogue, the curators argue: “Cleanliness is a fundamental norm of civility, and as a cultural value, it defines social positions, social differences, social duties. (…) The processes of ‘hygienisation’ are associated with the field of social re-education, standards of hygiene in cities, treating our own bodies and diseases, and urban sanitation. Naturally, for the process of ‘hygienisation’ to truly succeed one must clean the ‘human mind’.” This is offered by the exhibition Pretty Dirty, for which the seven curators selected work by fourteen artists. The catalogue presents seven different interpretations and approaches to the issue of personal hygiene, which can be complemented by the viewer’s own perception.

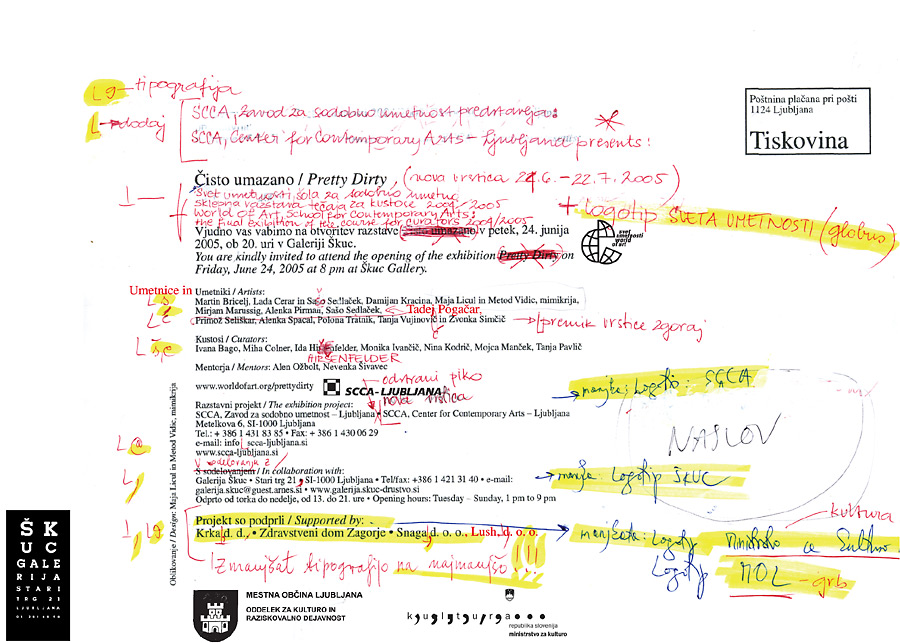

Maja Licul and Metod Vidic, mimicry, collaborated with the curators in a particular way, creating an exhibition-specific project of designing the publication and invitation to the exhibition. Maja Licul described the Effective Interest Rate (2005) project as profit that the artists have from engaging with the project, which began with cleaning a bank in 1994. This is the reason the curators selected Licul, but due to the poor photographic documentation, the artist proposed that she “takes care of the visual communication of the Pretty Dirty exhibition.” She was prepared to “assume a pedagogical role and guide the curators through a series of considerations about promoting the show; they agreed on her concluding a contract with each curator for services worth 130 Euros”. This was written on a line chart drawn by Licul on a wall in the exhibition, displaying the intensity of activities between the artists and curators on a timeline (the artists recorded in writing all the meetings). The first entry is dated 5 May 2005, when they first met, and the last is dated 20 June 2005, when the collaboration ended. The line fluctuates greatly, and has two peaks: the first around 10 May, when the first arrangements and discussions were taking place; from 20 to 25 May, the line is completely flat at the bottom, when Maja Licul describes the curators as flaccid; then the line gradually picks up, reaching its second peak and “falling” to an average by the time of the opening.

The catalogue is printed on a waste paper, with the text being printed on the previously unprinted side, and with black-and-white reproductions of the works on show on colour backgrounds being printed on the used, dirty side (tea packaging).

In the end, designing a catalogue means fine-tuning irregularities, eliminating mistakes and checking, while in this case, in line with the concept of the exhibition, the artists kept all the corrections visible. Red ink is used for typos, which pollute the standard language. On the invitation, one side also featured corrections in red and fluorescent yellow marking, while there is a “clean” version on the other side. The reader can choose either to enjoy the “dirt” of errors and corrections and the chaos of arrows and comments, or simply to turn the sheet over so that the eye can rest on the neutral clean print, which unambiguously and clearly presents basic information about the exhibition opening.

Linguistic purity is also examined by the project entitled Arcticae Horulae (1995−1998) by Alenka Pirman. This dictionary of German loanwords connected with art and science prompted widespread discussion in the media, public and among experts. In the introduction, Nevenka Šivavec highlights the significant influence of German on Slovene, adding: “For a purist, calques are horrible words, while Pirman has great fun with them. (…) Some words which have completely passed into general currency are difficult to give up in informal speech and, Pirman asks why we should give them up.”

Today, it is more relevant than ever to ask to what extent, and whether it makes sense, to purify a language, as Slovene is in greater danger from words borrowed from English than German. To some extent, words from foreign languages can enrich a language, but constant pre-emptive measures must be taken to prevent Slovene from becoming pretty dirty.

The first association a visitor to the exhibition has is of bodily hygiene, the obsession of contemporary humans with trying to promptly wash away the dirt of the city every day, the radiation of the computer screen and exhaust gasses. The twenty-first century calls for an immaculate, perfect, clean and attractive individual, who is convinced by cosmetic corporations of the need to use deodorants, make-up, hair dyes, anti-ageing creams …

Polona Tratnik also prepared a special project for this exhibition in collaboration with the curators (in a specific way similar to that of Maja Licul and Metod Vidic) entitled In-time. In this installation in progress (2005), personal items with the curators’ micro-flora were exhibited: Monika’s glasses, Mojca’s thousand-tolar note, Ivana’s razor, Nina’s toothbrush, Miha’s deodorant, Tanja’s contraception pills, and Ida’s CD. The objects are overgrown with the curators’ bacteria, spurring an association of the kinds of bacteria and their authentic habitats.

We are horrified when seeing bacteria on food, but overgrown human bacteria on objects in a gallery are somewhat aestheticised, highlighting that there are also good micro-organisms which are sometimes over-washed by aggressive chemicals, which do not allow the skin to defend itself naturally. The presence of bacteria quickly becomes an obsession, and constant washing a disease. What, then, is the basic level of hygiene? Who sets it?

The obsession with personal hygiene and ideal appearance Plasma by Stigmata (2003) is questioned by Tanja Vujinović and Zvonka Simčič with fictitious perfume, useless due to poisonous substances, who exhibit bottles with spray nozzles and testers for men and women. The cosmetic industry must persuade consumers that the “their bodily nature is seriously deficient and, due to innate processes of excretion and ageing, destined to stink and decay (…) Plasma by Stigmata is a fictitious perfume, an imagined smell, an unreal product (…) Advertisements for the perfume featured a perfect woman which combined the ideal of a film actress and a Renaissance painting,” writes curator Ida Hiršenfelder. Just as aggressive media advertising convinces us that a fragrance will make us more confident, satisfied and happier, the artists ascribe to their perfume positive qualities, including the disinfection and destruction of herpes, hepatitis B viruses, HIV etc.

Bodily hygiene was also the subject of the installation in progress by

Primož Seliškar entitled The Bather (2005), which was intended to disappear before the viewers. The project was produced for this exhibition. A soap cast figurine was placed under a driping water washing it away to

self-destruction (as of 2 July when the project was still in the making, the figure had still not arrived etc.). Water has always been used to wash away dirt from humans and also for spiritual re-birth. In her text, curator

Monika Ivančič argues that in “contemporary consumer society, soap is a stronger symbol for cleanliness” and that Seliškar “transformed water, a symbol of life into a force of destruction”. A person washes away sins and virtues, the number of which is (like Seliškar’s The Bather) decreasing. The emerging “disappearing” installation also poses the question of the transience of artistic work or the art system.

In the project Toilets, Made in India (2004) Lada Cerar and Sašo Sedlaček showed five types of toilet on embroideries. “The artists show that standards of hygiene are closely conditioned by the cultural environment, and present five national characters on the basis of different types of toilets and methods of flushing shit,” says curator Ida Hiršenfelder.

In addition to waste water and sewage, landfills constitute a big problem in cities, where the artist Sašo Sedlaček positions his video Picnic at the Landfill (2004). In an artistic action at the Ljubljana landfill, the participants suffered from the incredible stench. First, they prepared a snack, and the only advantage of the selected location was that they could throw litter anywhere without feeling guilty, even with some satisfaction, because they were, after all, at a landfill. They used plastic cups and disposable trays; the table was covered with black plastic, stressing the environmental effects of the easy living. The greatest paradox is that a large part of the landfill is full of packaging for cleaning agents. Micro hygiene causes macro pollution. “The fact that the existing ideals and norms for cleanliness are completely fantasmatic is even further emphasized by the inscription extending on the rubbish hill of the Ljubljana dump: Hollywood,” writes curator Ida Hiršenfelder in the catalogue.

By selecting the project Self-portrait by Alenka Spacal (2002, selection) the curators drew attention to other forms of hygiene. “In Self-portrait, the artist uses an autobiographical method to question and clean her subjectivity via various identities that she changes over time, and via dispositions,” argued the curators in a text on the exhibition. The self-portraits on tea towels examine five images of the artist – in a spasm, with a look of horror and bewilderment. She paints herself screaming, with her mouth tied, a patch over her mouth etc. The works are attached to a washing-line with pegs. The project can be read as a critique of the social role of women who, as housewives, are supposed to take care of the family’s bodily hygiene and the cleanliness of the home.

The phenomenon of household hygiene is also examined by Damijan Kracina in his video The Ant (1997). We watch “an insect which in the categorisation of living creatures on Earth is understood as an intruder, a parasite in human habitat (…). An ant can penetrate urban, closed, sterile human premises, and this ability to cross borders classifies it as dirt, something that has to be removed in order to re-establish order,” argues curator Ivana Bago. The video is screened on a miniature screen built in a gallery wall at a height of 50 centimetres, so we have to bend over in order to watch an ant die on sticky poison. Humans approve of killing insects, while their reaction is quite opposite with regard to killing larger animals. The artist magnifies the ant to such an extent that we can clearly see its antennae, the opening of the mandibles, the trembling of the legs, and the movement of the gaster. Are we shaken when watching a dying ant, or do we only take advantage of the video to carefully study the anatomy of this fascinating animal?

The painting by Mirjam Marussig Untitled (from the Intimacy series, 2004) explores “the gap between the intimate and the public with regard to the issue of moral hygiene,” write the curators. Fingers move along rosary beads, and by meditatively repeating words, a person becomes free of everyday thoughts, questions their conscience, and is spiritually purified.

In the video Golden Shoes of Times Square (2002) Tadej Pogačar touches upon political hygiene. As the author of the video writes, in 1990 the mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani, “cleaned” the centre of the city – an area which had previously been a symbolic place of the sex industry – with a series of restrictive laws in the name of health and safety. In the catalogue, curator Miha Colner explains that Pogačar’s action “was visible only to a careful passer-by, as the performer blended with the multitude of visitors and tourists. He walked around the square dragging a pair of women’s golden shoes behind him on a string”. Indirectly, the author highlights prostitution (“gold” high heels are a symbol of prostitutes) and human trafficking.

The only work at the exhibition visible from the street (originally it had been intended for installation in the street) is the multi-disciplinary project Fake Up (2003). Martin Bricelj with two City Lights banners presents a seeming disaster: four fictitious victims of biochemical weapons. “The project responds to the dirty media construction of reality. With clear results (strong response from the media and public), it warns of how dangerous manipulating the truth and hiding the facts can be. (…) The media were served with a street exhibition The Images of Horror, which was organised in Ljubljana by the newly opened office of Avbia – the Association of Victims of Biochemical Assault. (…) Fake Up used the media in the same way they use their audience (…),” wrote curator Nina Kodrič. Therefore, it is a question of a “hygienic minimuma”, which should be adhered to by the media.

The hygienic minimum or objective “hygienisation” at all levels of human activity is what the young curators sought to reveal via different artistic concepts and commentaries, where the issue was left open to the point that visitors could complement, research and project their views on their own.

The course for curators at the SCCA–Ljubljana concluded with a show, which, according to the curators, was successful. Beginner’s and technical shortcomings are a normal part of the learning process, which is what this exhibition is primarily about. Perhaps it would be interesting to expand the course for curators and connect it with a seminar on writing also a part of the World of Art, as this would result in a more comprehensive educational programme.

First published: Sandra Belšak, “Pretty Dirty, ‘Hygenisation’ through art practices in Slovenia”, Art Words, No. 71, 72 (Summer 2005), pp. 157–160.