Petja Grafenauer: interview with Saša Nabergoj

The World of Art, School for contemporary art SCCA−Ljubljana, has entered its thirteenth year in April 2010. From its inception, the course for curators of contemporary art – which has gradually developed into a school – has been an almost required post-graduate stop on the journey of a student wishing to become a curator. The majority of recognisable Slovenian curators who have been working in art since the 1990s encountered curatorial theory, methodology and practice for the first time at the World of Art school. The school has provided not only know-how, but also first contacts with artists, curators, critics and museum workers, and the systems of Slovenian and international art circles, while providing students with a safe research environment where the knowledge they acquired could be tested and used in the group process of preparing, executing, documenting and reflecting on exhibition projects.

It could be said that the World of Art has a monopoly on the education of future curators in Slovenia, but any reservations about a possible hegemony of a discourse – which could quickly emerge nationally due to the specific nature of Slovenia – are unfounded. The analytical spirit, self-reflection and keeping up with changes and needs in art – which are expected from students and the of World of Art team by the head of the school, Saša Nabergoj – promote continuous modifications to the study programme. This prevents the World of Art from becoming outdated and establishing a dominant educational discourse in the field of curatorial work in Slovenia and the region. The thirteenth year is again the result of the successes and failures of the past, and the attention of the team remains focused primarily on the professional needs of the participants. In addition to the tried and tested programme, there is new content which enables future curators to work independently, and particularly teaches them an appropriate way of cooperating with artists.

The World of Art is a programme intended for practical and theoretical education in the field of contemporary art. Can you say more about its beginnings and the first year?

It began in the mid-nineties (in 1996), when there were only a few younger curators in Slovenia, but many talented artists, exhibitions, symposia and prominent guests visiting the country. It was a very lively scene and the lack of young people working as curators was very noticeable. Therefore, Alenka Pirman, (who was then the programme head at Škuc Gallery), together with Lilijana Stepančič (Director of the Soros Center for Contemporary Arts – the predecessor of SCCA−Ljubljana), who was familiar with international curatorial programmes, had the idea of organising a course for curators in Ljubljana with a series of lectures. This was intended to teach the participants some basic knowledge about advances in the world of art. In the first year, the themes of the lectures were linked to the conceptual practices of the 1960s, because we were convinced that this period was vital for the production of art in the 1990s.

The format of the course was similar to that established several years previously by De Appel in Amsterdam as the Curatorial Training Programme. We sought to give the participants an apparatus of skills and knowledge which would enable them to work in the field of contemporary art. Most of the participants were art historians from Ljubljana University, which means that during their studies they had not encountered contemporary and modern art, but explored Gothic, Baroque and Renaissance art. Contemporary art was completely foreign to them.

The course presented situations in which future curators could test all the aspects of work in theory and practice: the methodology of research and production work, finding a concept for an exhibition, and practical skills, including PR, fund-raising etc. The students were included in a group, which promoted dialogue – whereas the study of art history here in Slovenia is based on memorising information, not contemplation and dialogue. We established an intimate situation for dialogue within the group, introducing the participants to an approach to work which was new to them.

How did you experience the Slovenian art system in the late 1990s regarding the need for training, and what differences are there today, thirteen years later?

The programme was shaped by the specific period when it was conceived. In the workshops, the students thought about the role of the curator, changes in the art world, and how to use this knowledge in practice. Alenka Pirman and Lilijana Stepančič, who led the course in the first year, were active internationally. The network of Soros centres where Lilijana participated was vital to the establishment of Manifesta, a manifestation of contemporary art which heralded a different exhibition model in international art. Alenka headed a programme at Škuc Gallery which was international, but involved in the local environment, while she was also active as an artist. Together they were a good team, because they were able to pass on different levels of skills and know-how, which they then reflected in their own work.

What is your story within the World of Art?

I have been involved since its inception; I am some kind of constant element, although several people have participated for a longer time.

When the programme first started, I was finishing my studies in history of art, and was not satisfied with what I had learned. I was interested in contemporaneity, but did not know how to articulate that. The first thing that brought me closer to contemporary art was the call of the Museum of Modern Art in Ljubljana for tour guides in 1995. I applied, and the job helped me become acquainted with the art system, and to discover what it offered and what interested me. Alenka Pirman invited me to participate at Škuc Gallery, where the course was held. I was Alenka’s assistant; I coordinated the course and actively participated in it.

After that, Barbara Borčić, the next SCCA−Ljubljana director, invited Alenka and me to work under the aegis of the Soros Center, which co-financed the World of Art in the first year. The school is still operating as part of SCCA−Ljubljana, the successor to the Soros Center.

So the programme has always operated under the umbrella of an NGO, which means that, while raising funds is more difficult, it enables the school to respond quickly to changes, new events and phenomena in the art world. This year, we created a new format for the school based on past experience, achievements and failures, which will provide the basis for subsequent years.

Many former participants in the World of Art work successfully within the Slovene art system. Their engagement is partly the result of the course, but the course did emerge at significant moments, when shifts in discourse occurred, which then established themselves in Slovenian art, prompting the need for new personnel …

Today, there are several options, because contemporary art is an interdisciplinary field, and, for example, Maska’s seminar is complementary. But back then, ours was the only one. The World of Art put the students at the centre of contemporary art, where they could discover what interested them. Some decided that this was not being curators, and did not continue working in art, which is a completely legitimate choice. But those who remained interested are very well positioned in the art world. Institutions knew that we were training personnel who would be able to work with artists. For me, responsible work with artists is one of the imperatives of the course.

What I somewhat regret is that, at the outset, we sought to establish several independent curators in Slovenia, but the reasons for us failing in that regard lie not only within the programme. There are only a few independent curators, mainly because it is difficult to support oneself in this way. An institution offers a safer environment and a financial and organisational background. Independent curators must include numerous tasks in the process which have nothing to do with their expertise, and be able to cope in various roles and be “one-man bands”. Often this is also the case in institutions, but few of them work well at all levels and enable the curator to focus only on the content of an exhibition, selecting artists and developing the concept.

Working as a curator in an institution is not less worthy, but I feel there is a lack of independent curators to balance the system. Therefore, the Slovenian system still feels deficient – and I could go on …

As you say, the training takes place in a safe environment, but the final exhibitions prepared by the participants are public events. The media reviews of the World of Art show that the public mostly knows about the end product and not the educational process …

Precisely. The undue focus on the final exhibition is one of the problems I am still trying to resolve, but it is a logical one. The process is very valuable, but an intimate part of the operation of the group. At the same time, regrettably, the media look for spectacular events, and our programme is definitely too modest to spur any such interest. In my opinion, art is not democratic, but should be presented boutique-style; so our way of working seems correct.

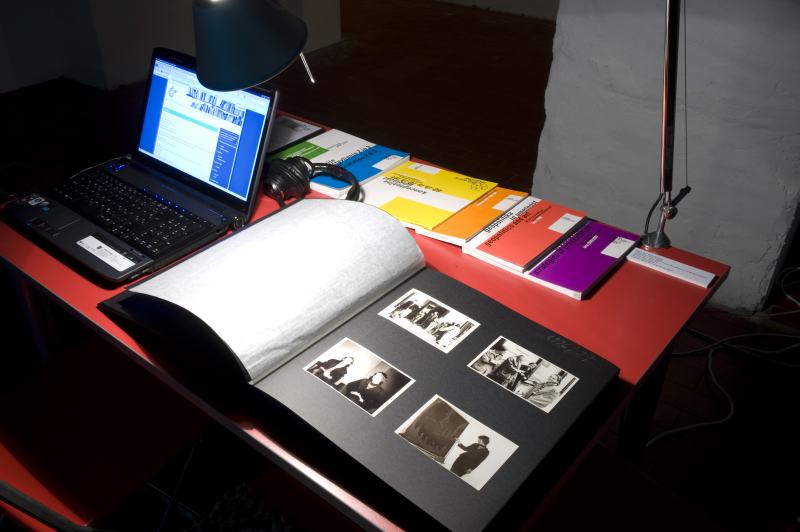

If we want to spur public interest, we need to be rather more innovative, which is why last year I prepared the exhibition Around the world of art in 4,380 days, which examined the previous years of the school, highlighting the process, which always remains hidden, although it could be very valuable to a wider public.

I believe that the significance of the final exhibitions lies in what the participants learn from them and use later. To me, the concluding exhibition is not an original work, like an exhibition by a curator already active in the world of art, but part of the study process that ends only by analysing the process and the exhibition, which is what a curator cannot usually do, as another exhibition is already underway. While the final exhibitions have received media coverage, the articles have not included a single real review. They are about the context, the school and the mentors, and the main focus was misdirected. I still miss reviews of the exhibition which would include a reflection on the selected works, the concept …

But this problem is not only typical of World of Art exhibitions …

Precisely! This is exactly what I wanted to say. Even in the case of the GESAMTKUNST Laibach 1980–1990 (MGLC, Ljubljana) exhibition, it is like that. The exhibition is an attempt at a different historicizing, a different historical positioning of key production in the Slovenian history of art. But has anyone highlighted that? No-one wrote about the production of art. The media reports about the Laibach phenomenon only as a phenomenon of a band performing with horns, drummers etc.

For the Around the world of art in 4,380 days project, you researched the history of the programme. What were its key landmarks, or how has the World of Art changed?

I cannot say that there were definite landmarks. Lecturers and workshop tutors brought different ideas, and always had many roles within the scope of the World of Art. This method of cooperation is the result of the way of working of the entire SCCA team and the former Soros Center.

One of the interesting moments was a conversation with Viktor Misiano, who prepared theoretical workshops on contemporary art with artists. It was interesting to hear how he strategically prepared the participants to talk about very interesting topics. He encouraged me to think about the meta-process of creating a school engaged with contemporary art.

The second signal came from Charles Harrison, who shared his experience of working in Art & Language group. He offered an interesting insight into the other side, the work of an artists’ collective, which again encouraged us to new ways of thinking and development.

All advancements within the World of Art seem gentle, processual and continual. They occur because we are always interested in who we are and what we do. Because we are included in the school’s process, while associating with guests, we come into contact with information which is often vital for curatorial training.

That things have not changed overnight is also obvious from this year’s different programme format, as you have looked for a suitable structure for several years. What are the key changes this year?

This year (2010), the World of Art is being held in two parts for the first time. The first part equips the participants with knowledge of art history, the methodology of reading and production research, while offering an insight into the world of art, which they can slowly begin to map on their own. The second part will feature what was once offered at the beginning: a course in curatorial practices and workshops in critical writing. We will soon be able to tell what the effects are, but I think we have managed to create a structure which enables us to focus more subtly on more complex issues later on.

In the late 1990s, Alenka Pirman and I drew up an interdisciplinary programme in a much less academic fashion. We wanted to create an open educational structure where active participants would provide initiative and independently express their views. But reality demanded that we change some paradigms. It became obvious that the participants needed somewhat more guidance, and the programme became more academic.

But the main changes are in content. The study of art history in Slovenia is some sort of logical predisposition for the job of the curator. However, even these students are not equipped with knowledge of modern and contemporary art, which is a necessary foundation for the study of curatorial practices. Every year, when researching artistic production, we have had to fight prejudice about contemporary art which we did not expect at this level. Although the situation was not foreseen, it meant that we first had to offer students such knowledge. Therefore, one of the key changes this year is that, together with Rebeka Vidrih, a new professor at the Department of Art History at the Faculty of Arts, who understands the need to include such content in the department’s curriculum, we prepared a series of lectures about the history of art from the avant-gardes to the present time. Also significant is a workshop on close reading, as it seeks to teach how, and not only what, to read. I myself only learned this gradually. These are major shifts and we will see how they are reflected in the work of the students.

As you have mentioned yourself, the World of Art is not a closed educational programme, but has always been actively connected with gallery venues and protagonists in the world of art. Not all schools work this way and I wonder how this method of work benefits the students.

This way of working has been SCCA−Ljubljana’s modus operandi from the very beginning. The practice was brought from the alternative 1980s by Barbara Borčić; Alenka Pirman operated in a similar way in the 1990s, and even today it is the key element of our work. Within the scope of the World of Art, students are shown the diversity of the Slovenian art system. This experience enables them a quick insight into the system, but, naturally, they must continue to develop their knowledge further.

Students go on study trips abroad, and foreign lecturers come to Ljubljana … How do you establish international connections and what are their essential characteristics?

Twelve years ago, we cooperated with colleagues from Zagreb and Bratislava who prepared similar study programmes for a year. Back then, funds were available from the Soros Center which were not intended only for the production of end-products. We could afford to send groups abroad to become acquainted with the international scene, and students established some contacts which are still relevant today. There were many short-term cooperation projects, but again the contacts were established with key individuals, in whom we recognised similar ways of thinking and working.

Today, the SCCA team still follows activities on the international art scene. We visit exhibitions, look for key issues, and collaboration takes place on such occasions. With a lack of funds, the only way to interest a person in coming to Slovenia is to meet them personally and interest them in the content that you are creating.

At present, we are again trying to establish international collaboration in a more structured way. For twelve years, we have been cooperating via enthusiastic individuals with the MA curatorial programme at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. Such long-term cooperation with people with whom we have come to speak the same language and developed a relationship for several years is essential for the programme, as views change and new projects emerge. The second programme, which will be incorporated into a structured platform, is the Krakow curatorial programme within the scope of the Institute of Art History. Despite the fact that the World of Art is run by an NGO, and the other two partners are programmes run by public institutions, we share similar problems, albeit stemming from a different history and environment.

Within the platform, student exchange will be significant, as it promotes different ways of thinking and precise discourse. Perhaps even more significant is the joint curriculum, in which each of the three schools will include the best parts of their current programmes. We want to avoid copying established comprehensive models, but research the content based on local issues and needs. Thus, the Austrian programme will offer knowledge of thinking in terms of space when installing a show, which is lacking in Slovenia. The curator must be aware of the features of the space where the exhibition takes place. There are too many badly installed shows lacking the curator’s conceptual reflection of the given space and knowledge of how to place art work in a gallery space.

Despite an active presence and the key significance of the programme for the art system in Slovenia, it seems that in terms of financing and infrastructure the World of Art is undernourished. Where do you find funding, because it is not a commercial programme and the tuition fees, in view of the knowledge on offer, are almost symbolic? Do you think that national and city funders are sufficiently aware of the significance of education in contemporary art?

I think that we are recognisable, but most funders believe that education and training belong in institutions, universities or museums, with which I have to disagree. Some issues tackled by our students are so immanent and specific to contemporary art that they require a different way of working than the one offered by a university or museum.

Other, greater funding issues are the same as with all NGOs. Grants are much too low. The Slovenian scene supports modesty. Distribution is fair, meaning that a similar amount of money is distributed to everyone, which is not enough for anyone to work.

The World of Art receives funding from the City of Ljubljana within the scope of the SCCA−Ljubljana programme and from the Ministry of Culture. The latter finds it difficult to understand that the programme is interdisciplinary, so it does not belong in only one single category included in the call. Therefore, we dissect it and apply to different calls – we try to find support within the professional training category, the final exhibition tries to get funding in the project category … Modest funding enables us to survive, but does not provide for a long-term conception of the World of Art.

The problem of funding is that the funders of the World of Art see it (and other SCCA programmes) as a project, which means that they do not support costs that are not directly linked to the programme, including the honorariums and fees for the World of Art team. Such a view underestimates the professionalism of the NGOs on the art scene. The World of Art brings together professionals who provide professional and excellent services even if they are not employed by a public institution, and, naturally, they expect payment. Yet there is not enough funding for an ambitious, multi-annual vision.

What are the key differences between the World of Art and other educational programmes, including De Appel, which is probably the most well-known?

The difference is in the ambitions, the purpose of training. De Appel trains students to work in the international “mainstream” art system. This has never been our intention. I believe that far more interesting things happen on the fringes, which are not necessarily limited to a geographic location. The advantage of the World of Art is that it allows for a strategy of small steps and modest proposals, which is also discussed by Charles Esche. I wish that the World of Art would educate individuals to work responsively in the world of art, but not necessarily to work in the limelight. We introduce our students to the system in a similar way as De Appel, but rather than finding possibilities for employment, I believe that it is necessary to show them different ways of working, to open their minds to understanding artistic production, to help them find their own place within the system and an appropriate way of cooperating with artists.

The World of Art has always been attended by foreign participants. Students from Croatia come every year, and the programme is well recognised and appreciated in Zagreb. Have you thought about transforming the World of Art into a completely international educational programme?

We have thought about that a great deal. Participants from Croatia brought interesting changes, as it led us to avoid many seemingly self-evident presuppositions. Due to their different background environment and the system of the study of art history, which in Croatia is a bit more contemporary and theoretically focused, these students are able to ask questions that our participants cannot.

The problem with a completely open international programme is the loss of a specific discourse, which is the result of working in a specific environment. Croatian students come to Ljubljana because they can follow the programme in Slovene. However, it is becoming obvious that mutual understanding of the two languages is disappearing. In an open international programme, the lingua franca would have to be English, which would be a great loss to the Slovene terminology. This is my greatest concern. Financial and logistical issues are nothing in relation to the terminological concern.

Even curators active in the world of art need new knowledge, which constantly changes and develops new content segments. Do you think that this need is recognised and expressed enough in Slovenia? Does the programme also work in this direction and, if yes, how?

I would be very happy to prepare more advanced courses, which would enable multilateral dialogue and the sharing of knowledge and views of art. With some workshops offered by the seminar, we tried to address this audience, as they were at such a professional level that they would mostly benefit people who have fully grasped the essentials. We wanted to create a platform for self-education, which would be based on dialogue. In its first year, our other programme, Studio 6, sought to bring together a group of curators which would develop an exhibition and discourse programme as a team. However, it turned out that active curators have little time. Art offers numerous possibilities, and active professionals dedicate their time to travelling, visiting exhibitions and conferences and researching current production to prepare new exhibitions …

But all these interesting conferences and wonderful exhibitions prevent us from occasionally taking the necessary break. Therefore, I still believe that the self-reflective educational process is urgently needed. In this way, artists and curators could avoid the traps of over-production and over-visiting, the all-encompassing cultural tourism, which I myself cannot avoid occasionally.

Last question: what is going on in the school now? What courses have the students had already and what awaits them this year?

We began the programme in April and are now in the middle of the introductory part focusing on art history. In addition to lectures on the history of 20th Century art and a workshop of close reading, the students have already visited numerous exhibitions, where they had the opportunity to talk to the artists and curators. We also took them to artists’ studios to familiarise themselves with the methodology of curatorial research and we hope that they will continue this on their own.

We are approaching summer, when participants will have to revise what they heard in the first part. The school will introduce some sort of a filter. Following additional selection, the second part of the programme will be attended by fewer students: those who are interested in continuing and have progressed in the first part. Together with tutors Jože Barši and Nevenka Šivavec, we will assess the work of students, also on the basis of their semester assignment – preparing a virtual exhibition with a concept and a selection of art works which have to be fictitiously positioned in a real gallery space. From this assignment we will be able to assess their knowledge, preferences and engagement.

The other part of the school year will focus on curatorial practices. It includes workshops on critical writing, which began several years after the course for curators, when the need for such education was identified. In addition to the introductory workshop by Miško Šuvaković, which is an introduction to the theory and art criticism, a number of workshops will take place in the second half of the school year. The workshops will also be open to outside participants, but the core will be our students, which means that they will be adapted to their level of knowledge and needs.

First published: “We are interested in ways of working based on local needs”, Petja Grafenauer: Interview with Saša Nabergoj, Artwords, No. 91 (Summer 2012), pp. 59–64.