Konstantin Akinsha

Notes on the underground

Art For Art's Sake

The phenomena of the Soviet unofficial art formed after the death of Stalin. It is possible to state that new trends in art were inspired by the beginning of the Khrushchev reforms. Cultural liberalisation became the sign of the times. Many young artists tried to escape the dead cannons of formal socialist realism. There were two sources which played major roles in the formation of "(an)other" art. One source, was the possibility of direct contact with the survivors; those who were the last representatives of the tradition of the Russian avant-garde. The second, was the flow of information that began to penetrate the Soviet from the West. The first generation of future underground artists were not interested in the radical forms of the past avant-garde tradition. The gurus of the 50s and the 60s, were such artists from the period of the forbidden avant-garde, such as Robert Falk, who was close to École de Paris, Alexander Tishler, with his soft poetic modernism, and David Shternberg. Their art coincided with the intentions of the new generation to create works free of ideology. The artists of the period wanted to produce an opposition to the official line of socialist realism. Their art was, by no means "dissident", in any sense. They tried to avoid political involvement, believing that it had been the destructive and deadly sin of official art. The slogan of the time was "Art for art's sake." The realisation of this program was limited by the usage of the moderate versions of the European modernism which had been recreated within the Soviet environment. The majority of the artists of the late 50s and the early 60s never could liberate themselves from the figurative nature of their art. It is interesting to note that such an artist as Anatoly Zverev, whose creativity was inspired by the first exhibitions of the American abstract expressionists, used this style for the manufacturing of his figurative works, though practically never crossing the border of abstract art. The so-called "soft modernism" of the 50s and the 60s was an important step forward for the Soviet artists, but it had more of a therapeutic value than an artistic value for the situation which pervaded in Soviet art. In an international context, this art was "forever late", and if it played a cleansing function for the Soviet Union, it hardly could be compared with the leading international trends of the time. But the initial period of the development of "(an)other" art was prematurely interrupted. The artists were sent underground not by their own will, but because of political developments. The same Khrushchev, who initiated the initial reforms, sternly refuted this "home-made" version of modernism. The famous exhibition at Manezh, (the main exhibition hall of the country) was finished by the scandal, thus becoming the starting point for the formation of the artistic underground. The exhibition included some works of the "(an)other artists" and the survivors of the avant-garde tradition. It was organised as a political provocation by the officials of the Union of Artists and the Art Academy. The representatives of the art-autarchy became nervous that these new trends might be supported by the state as a new artistic policy. They won and Khrushchev sternly attacked the "formalists". "(An)other" art had no other chance to begin its unofficial existence.

From Bulldozers to Conformity

During the late 60s and the first part of the 70s, underground art as

a lifestyle was beginning to be shaped. Very soon unofficial exhibitions,

organised initially in different clubs and scientific institutions, became

a very serious factor within the political arena. The rebellious artists

received their place within the formation of the dissident movement and

were used for purposes of ideological confrontations, both by the Western

propaganda institutions and their Soviet counterparts. The growing opposition

to the state was dictating more and more radical political steps. It also

influenced the essence of underground art. Such artists as Oscar Rabin,

who became a kind of Solzhenitsyn of the paint and brush, were beginning

to incorporate Soviet symbols and political narrative in their works making

them not only aesthetically unacceptable for the regime, but ideologically

dangerous. What can be seen as the final stand-off between the dissident

artists and angry officials was finished with the infamous "pogrom"

of the Bulldozer Exhibition,  when

an attempt, by a group of unofficial artists to organise an open-air exhibition

in Moscow, was brutally oppressed by the officials. The artists won international

support and found themselves on the front pages of the leading Western

newspapers, the Brezhnev regime, proved one more time, its barbarian essence.

If Khrushchev gave the initial impulse for the creation of the artistic

underground, his successor created its mythology. "Bulldozers versus

art works" - became the most powerful symbol of the cultural resistance,

exploited intensely by the nonconformist artists and Cold War propagandists

. The near total prohibition of exhibitions provoked the representatives

of the artistic underground to invent the heretofore, untraditional exhibition

form. So-called "apartment exhibitions" became the most popular

type of art display during the period of "stagnation" under

Brezhnev. Of course such exhibitions, which were, in many ways, reminiscent

of the demonstrations of the first Christian images in the Roman catacombs,

did not aim to reach even the slightest hint of professionalism in their

expositions. As in many elements of the day to day life of the artistic

underground, they were called to play symbolical roles - symbols were,

at that moment, more important than the realities they faced. Despite

the intensive press coverage in the West, the unofficial artists were

not recognised by the Western art world. Their political critique of the

regime combined with out of date and mimicked Western trends, didn't seem

to spark the interests nor did it look very appealing for the art "elite"

and professionals. It is possible to add here, that many vocal representatives

of the underground took an ultra-right political position which was balanced

somewhere between the integral anti-communism in true Barry Goldwater

fashion (a U.S. Republican senator from 1953-1986, he was the voice of

extreme right wing conservatism; a true "cold war warrior")

and Christian fundamentalism. It was difficult to await easy recognition

by the liberal international art world of people, playing such political

cards.The artistic underground lived in a dream world, imagining an ideal

West and feeding this imagination by visits to the Western embassies in

Moscow. These artists were surviving, thanks to the very peculiar art

market for unofficial art, which formed in Moscow in the beginning of

the 70s. This market even dictated the special size(s) of paintings which

were easy to take out or rather smuggle out of the country, these art

works became known as the "suitcase format." The majority of

the buyers were diplomats, representatives of the foreign intelligence

services, academics and international journalists. The black market rate

of exchange for the foreign currencies were giving a chance to the artists

to live somewhat prosperously.After the scandal of the Bulldozer Exhibition,

the officials permitted some representatives of the artistic underground,

to show their works publicly and tried to unite them in a kind of professional

organisation. Soon, new participants of this "semi-prohibited"

art, created a new trend, which could be described as the "nonconformist

Salon". They were manufacturing merciless kitsch based on "dissident"

narratives and surrealistic forms. For the majority of foreign visitors

and for the general public in the country at this time they became the

real champions of what was called "unofficial art". Their exhibitions

were highly popular and people waited for hours for the possibility to

see these new creations. It is not surprising that today's Russian art

critics are trying hard to forget about this page from art history - that

of the artistic dissent, which transformed into a strange form of the

nonconformist conformity.

when

an attempt, by a group of unofficial artists to organise an open-air exhibition

in Moscow, was brutally oppressed by the officials. The artists won international

support and found themselves on the front pages of the leading Western

newspapers, the Brezhnev regime, proved one more time, its barbarian essence.

If Khrushchev gave the initial impulse for the creation of the artistic

underground, his successor created its mythology. "Bulldozers versus

art works" - became the most powerful symbol of the cultural resistance,

exploited intensely by the nonconformist artists and Cold War propagandists

. The near total prohibition of exhibitions provoked the representatives

of the artistic underground to invent the heretofore, untraditional exhibition

form. So-called "apartment exhibitions" became the most popular

type of art display during the period of "stagnation" under

Brezhnev. Of course such exhibitions, which were, in many ways, reminiscent

of the demonstrations of the first Christian images in the Roman catacombs,

did not aim to reach even the slightest hint of professionalism in their

expositions. As in many elements of the day to day life of the artistic

underground, they were called to play symbolical roles - symbols were,

at that moment, more important than the realities they faced. Despite

the intensive press coverage in the West, the unofficial artists were

not recognised by the Western art world. Their political critique of the

regime combined with out of date and mimicked Western trends, didn't seem

to spark the interests nor did it look very appealing for the art "elite"

and professionals. It is possible to add here, that many vocal representatives

of the underground took an ultra-right political position which was balanced

somewhere between the integral anti-communism in true Barry Goldwater

fashion (a U.S. Republican senator from 1953-1986, he was the voice of

extreme right wing conservatism; a true "cold war warrior")

and Christian fundamentalism. It was difficult to await easy recognition

by the liberal international art world of people, playing such political

cards.The artistic underground lived in a dream world, imagining an ideal

West and feeding this imagination by visits to the Western embassies in

Moscow. These artists were surviving, thanks to the very peculiar art

market for unofficial art, which formed in Moscow in the beginning of

the 70s. This market even dictated the special size(s) of paintings which

were easy to take out or rather smuggle out of the country, these art

works became known as the "suitcase format." The majority of

the buyers were diplomats, representatives of the foreign intelligence

services, academics and international journalists. The black market rate

of exchange for the foreign currencies were giving a chance to the artists

to live somewhat prosperously.After the scandal of the Bulldozer Exhibition,

the officials permitted some representatives of the artistic underground,

to show their works publicly and tried to unite them in a kind of professional

organisation. Soon, new participants of this "semi-prohibited"

art, created a new trend, which could be described as the "nonconformist

Salon". They were manufacturing merciless kitsch based on "dissident"

narratives and surrealistic forms. For the majority of foreign visitors

and for the general public in the country at this time they became the

real champions of what was called "unofficial art". Their exhibitions

were highly popular and people waited for hours for the possibility to

see these new creations. It is not surprising that today's Russian art

critics are trying hard to forget about this page from art history - that

of the artistic dissent, which transformed into a strange form of the

nonconformist conformity.

Art As Literature

In the second part of the 1970s a new art movement formed in Moscow. This group has become the most interesting and successful branch of nonconformist art. They were the so-called "Moscow conceptualists". The group was lead by Ilya Kabakov, who later became practically the only Russian artists accepted by the "establishment" of the international art world. Many members of this movement combined official works for publishing companies with the unofficial leisure of underground art. Living in such a situation of, what could be called "double thinking", they preferred the quietness of their studios to the loud political manifestations of the hard-core artistic dissidents. The members of the first generation of the Moscow conceptualists succeeded to use their experience of the book illustrators for the establishment of the original art form of albums for example: Ilya Kabakov and Viktor Pivovarov. The albums, which became kind of "conceptualist" books, were the first step in the direction of a narrative form. Later, this passion for the interpretation of the world as a "story", was developed in the installations of Ilya Kabakov. The narrative form chosen by the conceptualists was the crucial break through for unofficial art and artists. They succeeded in telling the West about the harsh realities of the Soviet because their tale was translated into an understandable visual language and style. Even more radical attempt to adopt the Western forms of artistic expression was made by artists Vitaly Komar and Alexander Mellamid, who invented "Sots Art", which became the Soviet equivalent of American Pop art. Usage of Soviet symbols, which, in the context of that time, had openly ironic meanings, which practically guaranteed the artists possibility to be understood. In both cases the narrative was "local" and the visual form was appropriated and secondary. The last generation of unofficial artists formed in the late 70s and the beginning of the 80s. They saw their "teachers" in their direct predecessors and joined the group of Moscow conceptualists. This last generation preferred a more cynical game to that of the "serious" political dissent. It is possible to say that the main sources of creativity for such groups as "Mukhomori" were political jokes of the time (very often simply visualised in their works) and the texts of the Tartu School of Semiotics, the leading intellectual centre of non-Marxist philosophy in the country. For the young conceptualists both Lenin and Solzhenitsyn were no more than good material for ironic interpretations. The practice of their heroic predecessors, who took active roles in the ideological clashes with the authorities, transforming, at times, by physical fist fighting, were deconstructed by those in this ironic generation also. The exhibitions organised by the "Mukhomori ", called Apt-art were an open parody on the deadly serious attempts of their forefathers. In the mid 1980s, with the beginning of Gorbachev's perestroika, the new legend of the unofficial art was established. A so-called "Russian art boom", created by the Sotheby's and other auction houses, different western art dealers and curators, hurried to the Soviet Union trying to find new "exotic art" yet needed a strong supporting mythology. Such mythology was established quite soon. In the centre of the new pantheon of the "art of perestroika" was Ilya Kabakov, installed and surrounded by the supporting figures of the first generation of the Moscow conceptualists. These were artists such as Eric Bulatov, Ivan Chuikov etc. The young conceptualists received the role of the "chorus" in what seemed like a Greek tragedy of the perestroika art market. Kabakov's popularity in the West was connected not with his early works, but with the installations he began to create in many Western museums and exhibition halls. But, despite changing his media, Kabakov persisted with the main elements of his old style - the narrative. It is interesting that even the selection of the topics of his installations appear to unite him with the tradition of the 19th century Russian realist painters, who were selecting such subjects as "an apartment" or "a school" as preferable material for their social-critical exercises. Komar and Mellamid, who immigrated to America, also developed their style in a more narrative direction. The symbols of the "Evil Empire" couldn't work in an American context because of the simple fact that not all of those symbols which were used were recognisable to specific western audiences. The artists decided to create simulations of academic paintings which became a mixture of styles - that of the Bologna's Academy and those of socialist realism. The Soviet signs were replaced by Stalin, adored by the Muses. The brutal paintings of the early works were changed to the dark varnished "museum" style. The success of the Moscow conceptualists and Sots art was based on the introduction of a narrative form. Familiar 19th century "story telling" combined with recognisable contemporary art forms, guaranteed the possibility of being accepted by the international art establishment. The last chapter of "unofficial art", proved again, that Russia is the country of great literature.

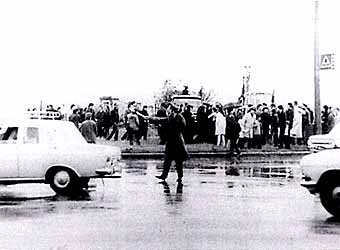

Photo:

- First Fall Open-Air Show of Paintings (The Bulldozer Exhibition), Moscow, September 15, 1974