Tadej Pogačar

P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. museum of contemporary art and new parasitism

This essay aims to present an overview of the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum of Contemporary Art and to explain briefly the strategy of its artistic activity, which we have called New Parasitism. By no means has writing it been an easy task, since it can be a fruitless exercise to analyse something that is in a state of continuous creative motion and constant transformation. We will therefore focus in the first section on some conceptual bases and artistic contexts, and in the second on a description of the actions carried out and projects realised in recent years.

This year's lecture series is entitled Theories of Display. This title should be taken in its broadest sense, to encompass artistic strategies, attitudes towards public exhibitions, and types of artistic production. Only the interweaving of gestures, discourse and behaviour can create the complete semantic network in which we are interested here (in contrast to the bipolarity of substance/form that attempts to capture the meaning of the works themselves). Just as a public presence within the art world is significant, so too can absence from the public eye be both significant and communicative. We are less interested in the "reality" of artistic practice than in its fiction - that is, the construction of fictive works that afford us an alternative view of reality and free us from our own blindness. It has often been observed that those who "create fiction" are the true realists.

How, therefore, do we define the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum of Contemporary Art? We can describe it as a notional, parallel art institution, a mobile spiritual entity which establishes specific interrelationships among a variety of subjects, societies, institutions, social groups and symbolic networks.The P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum of Contemporary Art does not have its own premises or staff, but rather adopts territories, chooses different spaces and feeds on the juices of established institutions. As a "parallel art institution" it serves: a) as a critical model for analysing the art-world system and the institutions within it, and b) as a framework for the introduction of alternative forms of communication and the establishment of new artistic connections. Its operations are based not on the production of objects or the analysis of situations, but primarily on the creation of happenings and the cultivation of relationships. The conceptual basis of the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum owes a debt to a variety of sources, one of the most important being without doubt the example set by Annali - the French school of new history. Our ethos can be condensed into three main tenets: transcending the limits of one's own discipline, flexibility and methodological eclecticism, and the practice of adopting and holding on.

The new French historiography has had a far-reaching influence on philosophy and art, leaving a decisive mark on situationism and the practices of those artists who have analysed the mechanisms and nature of contemporary society.

We have called the strategy of the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum's artistic pursuits New Parasitism - the adjective New pointing to the differences between parasitism as an ecological phenomenon and parasitism as a specific artistic practice (rather than solely a form of transcendence or institutionalised innovation).

Parasitism as an Ecological Phenomenon

In ecological terms, parasitism is a relationship between two or more species in which one (the parasite) lives off the energy of the other (the host). Whilst affording the parasite nourishment, enzymes, oxygen and so on, the host at the same time triggers various defence mechanisms against it. This creates a state of perpetual tension between the two. The parasite tries to overcome this conflict by finding new ways in which to maintains its connection with the host. It responds to mechanical and chemical reactions in the host (peristalsis, skin cleansing, antibodies) by anchoring itself to it (by hooks or suction) and then producing protective devices and substances that diminish the host's defensive capabilities.The development of aggressive/defensive mechanisms requires a great deal of energy on the part of the parasite, but because it lacks energy of its own, it survives by refining its defence mechanisms. The level of such refinement depends principally on the evolutionary age of the particular union(1). The natural environment of the parasite, particularly a species that is parasitic throughout its life, is the body of its host: to a parasite, a body is the outside environment. This inversion of "external" and "internal" is something with which the practice of New Parasitism, too, concerns itself.Parasitism in nature only rarely occurs in an entirely pure form. Transitional forms, including symbiosis and commensalism, depending on the ecological conditions, are more common. As a phenomenon of the ecosystem, parasitism is extremely positive in that it is a way of regulating populations. Of the 40,000 animal species to be found in the geographic territory of Central Europe, as many as 10,000 are parasites. This demonstrates the extremely common and widespread nature of the phenomenon of parasitism. New Parasitism differs from parasitism in nature in terms of its procedures. However, some ecological models remain relevant to activities in social and societal environments.

The Museum and Parallel Institutions in the System

For the past two centuries, the museum or gallery has been the art system's main institutional environment. It serves both as a framework for art and as a border between the codified, accepted and organised "interior" and the chaotic "exterior". In the past century it has even constituted a form of cross-section of dominating value systems and aesthetic objects characterising particular cultural territories. The museum continuously legitimises and at the same time reinforces the myth of objective historical representation, in which artwork assumes the role of document; this myth is based on a linear comprehension of time (and history), gradualism (the idea of gradual, logical progression) and a clear future direction.The basic motif of avant-gardes of the past (the Russian Avant-garde, Futurism, Dadaism) has been a sharp revolt against the traditionalism of the museum, and against its status as the institutional showcase of bourgeois class culture. As Boris Groys points out, it is this radical protest that has, in the past, defined the avant-garde. The historical avant-garde cultivated two metaphors: that of art as life (social/political engagement) and that of the museum as death (the burial ground of culture). But these "negativist" programmes (Habermas) did not have the power of transformation and thus did not succeed in changing the system.In due course, museums accepted and exhibited the avant-garde, thereby neutralising and paralysing their "external opposition". This dark scenario nevertheless has its bright side: the historical avant-garde has "survived" to the present time, if only because the museum system (paradoxically) took it under its wing. Without the museum system it would not have been "preserved" as we know it today: as an external living art, as the living dead ... Dracula(2).

From the first decades of this century onwards, we can trace several strategies which undermine, problematise, deconstruct or call into question the structure, ideology, mechanics and spatial presentation of art. These strategies differ from the direct assault advocated by the historical avant-garde in that they create, as it were, a "point of intersection" with the artistic system enshrined by museums and galleries. Usually they involve reconfiguration or rearticulation of that which is contested, in a critical or parodying manner. In short, they represent a transition from out-and-out opposition to "critical action".

The so-called parallel institutions within the art system that have emerged over recent decades have their antecedents in Duchamp's Société Anonyme, Warhol's Factory, Broodthaers's Museum of Modern Art or Beuys's open international university. In response to the question of whether culture would continue to bear any real significance for society, Broodthaers replied that it could only survive by "embodying itself", with its own reference sources and theory with which to counter the images and texts circulating in the press and other mass media - the ones that currently determine the rules and patterns of our behaviour and ideology. Parallel, fictive institutions represent a response to this situation. But characteristic of many of them is a fascination with planning, organisation, production and distribution - elements normally associated with the economic sphere. In the late capitalist period, economics have become the main, dominant social value and the overriding discourse. The economy has taken over the position traditionally held by religion. Parallel to this, it has brought about a diversion from the concept of author/artist; by its very essence it undermines and breaks down the logic of the art system that rests on the notion of originality and the autonomy of the subject.

The new generation of artists have radicalised this problem still further. They have created a kind of perverse dialectic between anonymity and stardom, presence and absence, a logic that can be related to the logo of an organisation. We can now speak of the "aesthetic" of organisations and of institutional "values", since the logo represents both the physical institution and the ethos it employs in holding dominion over a specific territory. Reality is administered and distributed in accordance with these so-called institutional criteria. Within this system, artists are employing elements of mimicry and camouflage, and with them creating new, and mixing old, groups of symbols. Since the late 1980s their output has become a criticism of, and at the same time a fusion with, the system(3).So an art institution can now be a bank (Banca di Oklahoma Srl), an airline company (Ingold Airlines), an agency exploiting new possibilities in the art of the funeral (ENIO), a chain of companies selling cultural products (Mc Jesus Chain), or a fish company (Fish-handel Servaas & Son) which packages, preserves and distributes "fish air".

No Event Performances

No Event Performances - performances independent of any event - was the name we gave to our early activities, some of which were carried out before the formal establishment of the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum of Contemporary Art. The public were not informed of these, nor were they present at them. The performances were carried out anonymously, in both public and private spaces, in the city and in the countryside. Most of them have been only modestly documented.

One example is an early performance called New Spring Collection (1979), an ironic fashion show held at a suburban rubbish tip near Ljubljana. The rubbish and scrap formed a dramatic backdrop to the graceful stride and co-ordinated choreography of the fashion show. The performance was carried out anonymously and is to be repeated every twenty years.

Visit

I (1981) and Visit II (1993) were anonymous performances carried

out within a museum. The performances aimed to deepen the empathetic relationship

with the artefacts exhibited in the museum. To this end they used elements

of enhanced communication, dialogue, accustomisation, experiences. Visit

II, a performance at the Natural Science Museum in Ljubljana, has

been documented in three photographs: Meditating with a Mammoth, Sleeping

with a Deer and Feeding a Bear.  The

performances took place without an audience, intimately, and in complete

silence.The Travelling Globes (1990) performance exposed the semantic

transformation experienced by an object when changing location and context.

Documented by photographic snapshots, two demonstration globes "travelled"

a planned route, posing as public sculptures, everyday objects, aesthetic

objects and school models, finally ending up as a works of art in a public

collection.The Panorama action was carried out in cooperation with a group

of children, who painted long rolls of paper that were later wrapped around

treetops, creating an interesting interplay between different models of

nature.

The

performances took place without an audience, intimately, and in complete

silence.The Travelling Globes (1990) performance exposed the semantic

transformation experienced by an object when changing location and context.

Documented by photographic snapshots, two demonstration globes "travelled"

a planned route, posing as public sculptures, everyday objects, aesthetic

objects and school models, finally ending up as a works of art in a public

collection.The Panorama action was carried out in cooperation with a group

of children, who painted long rolls of paper that were later wrapped around

treetops, creating an interesting interplay between different models of

nature.

Laboratorium I (1993) involved a performance and installation in undisclosed private premises. They were not directly on view to the public, but information on the performance and installation was relayed later in the form of an explanatory text and selected documents. This project exposed the problems of information, its manipulation and documentation. Laboratorium I tells the following story: an experiment is performed in secrecy. A mistake occurs whilst it is being carried out (mistaken suppositions, the human factor, mix-ups) and the experiment ends unsuccessfully, with catastrophic consequences (the total destruction of the laboratory's equipment and interior).Because no information on the preparations for the experiment or on its execution had been passed on to the public, it had no existence whatsoever in the "public domain". This situation made it possible for us to reconfigure the past freely in order to satisfy current interests, an approach widely used in political and economic spheres. With the installation Laboratorium II (1994), the project underwent a symbolictransformation in the form of its reconstruction in a museum / gallery. What we were interested in here was how a certain "event" becomes transformed through reconstruction, its symbolic gains and losses. We were investigating the clash of two institutions which both represent behaviour and knowledge, the laboratory and the museum - the first a space of direct experience, the second a space of accepted norms.

New Endoparasitism

Under the classification of New Endoparasitism we undertake projects that are characterised by the "building of nests" in various institutions, such as museums and schools. Constructed by rearranging internal elements found at the location itself (information systems, architectural elements, historical and social contexts, artefacts, texts, etc.), these create new readings and communication.

These projects are: Art History - Through the Body (1994), West-Side-Story (1994), Evolutionary - Notes on Human Behaviour and Progress (1996), School's Out (1997) and Exhibition of Exhibitions (1998).

The Art History - Through the Body project was created at the premises of the Museum of Recent History in Ljubljana. At this time, the museum was just concluding comprehensive, several-year-long preparations for a new permanent display that was to present a complex evaluation and interpretation of the national history of the past century. The P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum's project was thus realised at a time when the Museum of Recent History found itself in an unusual (crisis) situation; a period in which recent history had not yet been constructed, and the older history was losing validity. The display originated from the location of the institution itself and its historical context and sociological position, but what was most significant was the process of selecting the artefacts and museum objects and the strategy employed in displaying them.In the pieces we selected we traced the concept of the body, in two directions: the body as an index of the disappearance of the individual into the symbolic web of ideology, the masses, the collective; and the body as a physical entity devoid of symbolisation (e.g. wound, torture, extreme emotional states).

The project was created through daily visits to the storage facilities, offices and exhibition sites, yet one of its key components was the physical presence of the director of the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum during the preparations and for the duration of the display. The display took up five rooms of the museum. In each a complete story, narrated in a non-linear fashion, was told as part of an open series. The last room was occupied by the "Administration of the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum of Contemporary Art". The administrative offices of an institution, usually carefully hidden from the public eye, could be experienced here as a public room of communication (guidance through the exhibition) and an essential component of the complex display.

A similar approach marked the project entitled Evolutionary - Notes on Human Behaviour and Progress, realised in the Boijmans van Beuningen and Naturmuseum in Rotterdam, within the framework of the new European biennial Manifesta I. In the Boijmans van Beuningen and Naturmuseum we selected as our territory the corridor that links the building's facilities, which is not normally intended for display purposes. This location was chosen as one which has the function of connecting things in the museum and is arbitrary in nature. We covered the walls of the hallway with green panels, thus both visually and physically separating it from the other rooms. The project was directed towards an investigation of what is actually represented by "Europeanism", that is, what it constitutes. From the museum depot we selected a group of photographs of contemporary European and American artists and mixed them with works by the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum (mostly cover images from science and fashion magazines). All these items were framed, in the workshops of the museum, in such a way that the passing visitor could not separate the "virus" pieces from the "real thing". We hung the photographic works in the green corridor and displayed them in distinct thematic groups (city, women, scientists, animals). To this visual material we added text, comprising a series of carefully selected quotations made in Europe over the past two centuries - all allied to theories and concepts of evolution developed within the anthropological and natural sciences (e.g. craniometry, creationism, neo-Darwinism). The choice of quotations was selective; we were interested above all in those which revealed, in the most direct and crude manner, stereotypes, complexes, cultural prejudices, morals, passions - everything that normally lies concealed and stifled by objective science. The criterion for selection was therefore not scientific justification, intellectual persuasion and the like, but the desire for domination and power that is brought to the forefront in these hidden thoughts.

The objective of the second part of the project was to present the main curators of Manifesta I as the most important links in the systemic chain. They were each sent a written invitation to sign the "Rotterdam Declaration", under the terms of which they would participate in a hypothetical DNA fingerprint study to be carried out by a professional biologist. This would provide us with a genetic record of each of the curators. A lack of cooperation on the part of the curators meant that the study was never realised. The School's Out project was prepared at a Ljubljana high school with the help of pupils and a well-known disc jockey. Discreet interventions in the school's classrooms did not interrupt the regular rhythm of lessons and visitors could only view the project in the recess periods during school breaks. The displays and works crossed and juxtaposed elements of education, domination and discipline with visual elements and systems of knowledge. We used teaching tools and school aids found at the location itself. The project began with a disc jockey party and concluded with a discussion about the project.

Fake and Fiction

In a similar way to other art institutions, every few years or so we prepare a display of newly acquired works in our collection. The Recent Acquisitions project (1996) in the Škuc Gallery played around with the overall apparatus of the museum and exhibition system: from publications, broadcasts and announcements in the media, through the ritual of the official opening, to the presentation and interpretation of the works. Most of the information that was distributed about the exhibition was unreal and fictitious.

The exhibition was to present pieces by five young artists that had been selected by Dr Pamura Umetessi and purchased by us. At their own request, the artists would remain anonymous. All the supplementary explanatory apparatus of the exhibition, such as the legends placed next to the exhibits, was created from random cuttings (fragments of completely different texts being reassembled into a new, "nonsensical" whole) and had no connection whatever with the works on display in the exhibition (something which the majority of visitors did not even notice!).

Alongside the exhibition we organised conventional guided tours, engaging a group of young art historians to carry out this task. Following instructions from the director of the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum, each of them was to prepare his or her own story, version or interpretation of the works. The guides were also to incorporate into their narrative the field they had best mastered, applying this knowledge to the exhibited works. In this way, the narration (and interpretation) became completely open, the various stories carrying equal weight in spite of using utterly different references; the "authenticity" of the statements made was assured by the framework of the museum institution.In conjunction with the exhibition, a museum shop selling selected products and graphic prints was opened. Simultaneously, the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Product Corporation was founded. In the future it will cover the financial aspects of the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum's operations.

Communication Networks

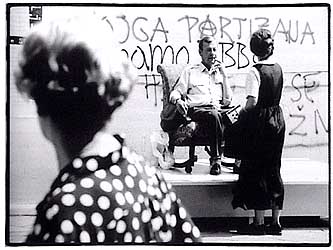

The establishment of parallel communication networks is an important activity of the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum. Because the Museum does not have its own staff, it occasionally hires, on a temporary basis, collaborators, professionals and experts who, for a specific period of time, acquire the status of museum workers and associates.Kings of the Street (1995-97) was an art project that brought together a number of professionals (a photographer, an architect, a social worker), the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum and marginalised individuals from the city centre - i.e. the homeless.As Pamura Umetessi wrote in the catalogue accompanying the project, Kings of the Street offered a new model for establishing connections and communication as a basic armoury. The project was therefore neither a social commentary nor an artistic event carrying a symbolic message, but a complex undertaking directed towards motivating and enabling urban minorities, using a combination of media and tactics(4). The project culminated in a one-day street campaign. This began with the official signing of a contract of mutual cooperation and also determined the financial arrangements of the agreement. By giving their signature, the homeless committed themselves to actively participating in the campaign, and for this they received a symbolic payment. Armchairs were placed on podiums (thus elevating the participants in relation to the passers-by) around the city centre. The homeless individuals sat in these armchairs and entered into conversation with the townsfolk - no longer as anonymous individuals, but as representatives of a marginal social group and co-authors of the project.Kings of the Street is the first of a trilogy of projects which lay emphasis on collaborating with marginal groups that develop unique, parallel forms of economics for their survival.The P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Archives and P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Security projects (1998) also entailed direct communication and cooperation with the public (visitors to galleries and museums).

In view of the inadequate records and supervision of visitors to public institutions, the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum devised a method for exerting greater control. This took the form of museum staff collecting visitors' fingerprints. In return for a fingerprint (an original visual record) visitors received a copy of a graphic print from the Museum's collection. The second phase of the project will see the fingerprints analysed, professionally systematised and in this form put on public display as an open, public archive on the Internet(5). This undertaking by the P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum directly questions the issue of identity, the concept of individuality, and relations between the law, power and control.

Notes:

(1) Kazimir Tarman, Osnove ekologije in ekologija živali, Ljubljana 1992.

(2) Boris Groys, Das Reich der lebendigen Toten: Avantgarde und Museum, Jahresring 40, 1993.

(3) Marc-Olivier Wahler, Rapports d'entreprises, Art press 230, dec. 1997.

(4) Pamura Umetessi, Kings of the Streets, Journal for Anthropology and New Parasitism, 1.3, No. 1, 1996.

(5)See P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum's homepage at www.ljudmila.org/scca/parasite

Photos:

- Tadej Pogačar & P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Muzej sodobne umetnosti, New Spring Collection, 1979

- Tadej Pogačar & P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Muzej sodobne umetnosti, Visit II (Sleeping with a Deer), 1993

- Tadej Pogačar & P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Muzej sodobne umetnosti, Laboratorium I, 1993

- Tadej Pogačar & P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Muzej sodobne umetnosti, Kings of the Street, 1995