Igor Zabel

Exhibition Strategies in the Nineties: A Few Examples from Slovenia

Introductory note

"Strategy" is a word we tend to use with some frequency and sovereignty when talking about contemporary art, e.g. "art strategies", "the strategy of audience relations", "exhibition strategies" and in similar contexts. These and comparable words have become such an obvious component of artistic jargon that we consider their meanings obvious as well. Still, perhaps it would not be entirely out of place here to begin by looking up the actual meaning of "strategy".

If we investigate the origin of the word, we see that it stems from the military. Such is also its etymology, as it originates from the Greek words stratos - army and agein - to lead; strategos therefore means military commander. Besides its narrower meaning of actually leading an army, the term "strategy" also encompasses the broader meaning of skillful and prudent handling of affairs in an unarmed battle, e.g. political, and finally in the figurative sense: of the serious handling of matters particularly those directed towards a purpose. It seems that it is this figurative meaning or term that fits the idea or concept of "the strategy of exhibiting". Nevertheless, the general usage of a term such as "strategy" certainly indicates that the art field is not neutral, that it is saturated with a kind of "agon", therefore competition, conflict or even struggle and that its main meaning (although not always entirely explicit) is also a "battlefield".

Exhibiting or displaying work that is on view for the public always implies a kind of strategic relationship, even if the work is wholly anonymous and self-contained and if the exhibition space seems completely neutral (the so-called "white cube" for example, only seems neutral as it is related to a specific public, institutional network, group of experts and collectors). Art as such can only realize itself in relation to an audience and it is precisely in the act of defining this relationship that we unavoidably encounter a kind of global strategic idea, an idea that determines the individual aspects of the work appearing in public, from the "exhibition design" details (the position, lighting, dominant or marginal positions, etc.) to the question of which institutional (or non-institutional) space to mount the work in, for which public it is primarily targeted, and the like. In short, in the most general sense of the term, "exhibition strategy" is this global concept, a sensible collection of procedures and approaches aimed at ensuring that the work will be seen in the right light by the right viewer.

In this essay, I do not intend to deal with this broader notion which is a component of every exhibition. I would rather confine myself to art that expounds and perhaps even incorporates this dimension in its effect. Such projects all consciously revoke the dualism between artwork and the act of exhibiting. In short, the work is no longer a kind of autonomous given for which suitable surroundings must be found and organised. Rather, it occurs within the tight and dynamic relationships between the artifacts, surroundings, viewer, curator, institutional framework and so on. Artists, work, surroundings, audience, institutions - these are not abstract entities, but are defined by ideological, political, class, gender, linguistic and other factors and their discrepancies; and this expounds the "agon" that among other things demands a strategic approach in exhibiting art.

I suppose this is the approach towards "exhibition strategies" that is particularly characteristic of what we call the "art in the nineties". By this, I do not mean to say that exhibition strategies are also entirely a thing of the nineties, on the contrary. The numerous strategic approaches appearing over these past few years were developed much earlier in the 80's, 70's and 60's and even earlier. The nineties have reaffirmed, appropriated and adapted these approaches and incorporated them into a different context and has given them a somewhat different meaning.

Up to now I have spoken about the strategic aspects of exhibitions as if they only concerned the artist in his or her relation towards the exhibition space, institutions and audience. But just as a field of "agon", the field of art is an area in which different interests cross paths, thus resulting in the development and cross-breeding of different strategies. When speaking about exhibition strategies, besides mentioning the artists, we must, at the very least, also mention the curator and exhibiting institution which in line with their strategic interests can also firmly define the context of an exhibition and manner of putting the work on display and in doing so this importantly influences the meaning of the work.

The Strategy of Exhibiting in a "White Cube": the Mala galerija Example

Over the past decades the notion of the art exhibition space had been essentially determined by the concept of the so-called "white cube". This was developed during the Modernist period as the ideal environment in which to view individual pieces of art which themselves were seen as self-contained, freestanding and autonomous entities. This is primarily a neutral space as independent as possible of external circumstances such as the time of day or the annual change of seasons. This includes the historical, political and social contexts. Harmonious architectural forms, white walls, neutral floors, evenly distributed and constant light (indirect or even artificial lighting) were thought to ensure that the works of art on view would achieve full expression on their own, as autonomous and purely aesthetical entities. With several examples taken from a single exhibition site - Ljubljana's Mala galerija (Small Gallery) - I would like to show how certain artists tackled the neutral and thus impersonal space (in many ways Mala galerija is the typical white cube), how they made use of its possibilities and at the same time perverted its neutrality and thus accentuated some of the possibilities of a strategic approach towards a "white" gallery such as this example.

The first case is that of Miroslaw Balka, who appropriated the space by means of a symbolic act: at the entrance of the gallery itself, he placed a "doorstep" made of material from his own burned-down studio in Ottwock. This doorstep functioned as a symbolic threshold turning the interior of the gallery into the artist's own personal space into which he moved a house (a metal construction based on his body's measurements). This transformation of space was necessary, because, among other things, Balka had transferred into it his own personal story linked to the real time of his exhibition - namely the period close to Christmas. (With this very act the artist rejected one of the fundamental requirements of the "white cube" - independence of external circumstances. The gallery's large windows - as the characteristic making the greatest departure from the ideal "white cube" - acquired a special role as a connection between the interior and exterior.) With the gallery space marked out in this way, the reality of the Christmas season was transformed through the artist's vision of winter as something hovering between good and evil so to speak; here winter on the one hand was shown as a time of want, suffering, death and destruction and on the other as a time of salvation, sublimity, new beginnings and mercy. (This dualism is present in the title of the exhibition itself: Winterhilfsverein. The title alludes to the suffering and dying during the Second World War, particularly in the winter, but also to the idea of solidarity and aid.) Through this transformation of the gallery space, the gallery's whiteness completely lost its impersonality and neutrality by acquiring a special, meaningful, emotionally and sensorial charged essence.

Petra Varl inhabited this space in a different manner. With a project dedicated to her mother, she completely annihilated the characteristics of the white cube: she covered the floor with linoleum and the walls with vividly colourful wallpaper, and placed elements belonging to the kitchen (a refrigerator, table, chairs) into this space. But this was not really a kitchen nor some truly intimate space. We could sooner say that the artist created a setting, a stage; in it by means of a system of selected objects and other elements (drawings, notes) functioning as signs, she literally staged a domestic environment or, at the very least, the personal experience of it. (The fact that two actors performed at the opening of the exhibition only further emphasised this theatrical dimension.)

Vadim Fiskin was confronted with a situation similar to Balka's: he was to mount his exhibition in a space that was empty, neutral and impersonal and which in itself did not offer him any points of support. And so his first step was to locate the space. Thus Fiskin marked the space's precise geographic coordinates on the gallery's floor. By doing this he not only installed the site in strict geographical terms, but an implicitly cultural one as well. At the same time he located his project in another way - institutionally. Meaning that through his approach to this exhibition he opened the issue of the gallery space and exhibition (in a dialogue with Viktor Missiano, the curator) as an institution. In line with this fundamental approach to the exhibition, which was the act of locating, he decided to take the term "one-man show" seriously and literally. Thus, he exhibited the entire body of work he had created up to that point by means of slide projections. As the curator of the exhibition, Viktor Missiano, too, set out his role analogously; he gave thought to the basic role of the curator and decided it was to pose questions. And so to the visitors of the exhibition he asked several questions concerning the exhibition, its author and the viewer's response towards them. In the middle of the gallery, at the very point determined by Fiskin's geographical coordinates, stood a wooden construction orientated to the four corners of the sky. This construction held the slide projectors that projected the artists' work onto the darkened walls of the gallery. If the viewer choose to step inside of it a light would switch on and a tape recorder relayed Missiano's questions and recorded the viewer's responses and in doing so, radically located and activated the viewer also.The gallery space continues to be an abstract, impersonal framework, yet always filled anew with content which subsequently disappears again.

Rene Rusjan reflected this invisible history of the gallery space in a project titled Yesterday, for example...in which she exhibited documentation of exhibitions which had been mounted during the previous years in the Mala galerija. She borrowed from two exhibitions which had been presented immediately prior to hers: an exhibition of the 'photo-ceramics' of Michelangelo Pistoletto and an exhibition by Uri Tzaig entitled Two Balls (she found the title for her exhibition in Tzaig's: the words appearing in the title were namely one of the subtitles of Tzaig's video film and accidentally appeared on a photo of the display). She kept the video projector and chairs for the viewers from Tzaig's exhibition only this time the screen showed a presentation of the exhibitions, vernissages and other events held in the gallery. At his exhibition, Pistoletto presented a series ofceramic plates bearing photos of pieces from his series the Oggetti in meno which he had created in the sixties; Rene Rusjan displayed similar plates with photographic representations of various past exhibitions held in the Mala galerija. And just as Pistoletto re-actualised his own works through transformation, "recycling" and, so to speak, re-appropriating them, so Rene Rusjan brought back to life certain past exhibitions and thus appropriating them, or in other words identifying with them and in a sense proclaiming them her own.

Ulf Rollof approached the gallery space and the institution of the exhibition in a somewhat different manner. The exhibition itself did not essentially modify the "white cube"; Rollof filled it rather densely with fir trees that were covered in wax and placed in concrete stands that allowed the trees to sway to and fro. In doing so, the artist exploited the whiteness and neutrality of the Mala galerija, of its "art", to emphasise the contrast with nature which itself had been subdued, reworked and turned into a toy. What is important here is that Rollof's project reached beyond the borders of the gallery and the exhibition. The artist realised the exhibition in Ljubljana; this production process which is normally concealed from the public was opened to an audience. Bart De Baere, who curated the exhibition, used three words to describe this expansion: production (therefore the process of creating the work); reception (the opening of the exhibition itself as a social event and also as the point at which the work is displayed before an audience); and exhibition (the exhibition and its life). He set up a temporary studio in one of the exhibition rooms of the Moderna galerija (Ljubljana Museum of Modern Art). By doing this he took an environment otherwise open to the public and rather than closing it, changed it into a half public and half private space, similar to the 19th century studio which was also a semi-public space, a space open to friends, art connoisseurs, critics and buyers, therefore a place for viewing, discussion and business transactions. Visitors to the gallery were able to walk into Rollof's studio, view his work, talk to him, sit down and leaf through catalogues and other material. Part of the exhibition was also realised in the open in front of the gallery. Thus the exhibition grew into a process that offered new opportunities for cooperation with the audience. At the same time, Rollof creatively made use of the practical aspects of the preparations for the exhibition by deconstructing the established principles of exhibition institutions and instead of the "white cube" affirmed a different example of exhibiting and communicating with the audience.

Art in Context

Art in the nineties is often no longer considered as a production of autonomous or even purely aesthetic pieces. It consciously operates within various social and historical contexts and establishes a reflexive or even directly active relation towards them. This does not necessarily mean that such pieces must be realised outside of the gallery; on the contrary, sometimes they make good use of the traditional exhibition site. For example, within these "neutral" exhibition surroundings it is possible to create different or even incompatible surroundings, whereby the effect of such pieces is often based on this incompatibility and incongruity of codes itself.

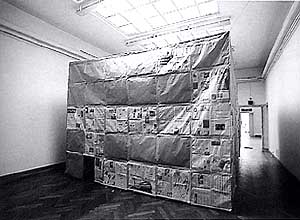

Earlier on I described how Miroslaw Balka had moved into the Mala galerija and set up his own symbolic "house". Rirkrit Tiravania placed a "house" within the gallery, too, however this house was somewhat different. Tiravania created his work of art for an exhibition titled The House in Time; the theme of the exhibition related to the issues of location and dislocation, home and exile and also to the experience of war refugees from the regions of former Yugoslavia with whom the issue of dislocation and exile had been confirmed in a particularly painfully concrete and radical way. When the artist received an invitation to participate in the exhibition he began to collect issues of The New York Times. He took out pages from the collected copies referring to the war in the former Yugoslavia and created a house out of them (and so he literally built a house of "time", namely a newspaper called "The Times"). He had therefore built another space within the gallery space. The visitor could enter it, make a cup of tea, sit comfortably and leaf through the newspaper pages not used by the artist to build the house. Tiravania therefore built the viewer a personal, intimate space, however literally building it out of time and history - conveyed through the newspaper as his eminent medium.

At the 2nd Triennial of Contemporary Slovene Art titled U3, Rene Rusjan also built an intimate area which was simultaneously a space of time and history. She closed-off part of the exhibition hall and organised a reading room. The visitor had access to diverse answers to questions she posed to a number of her acquaintances concerning the period of the past five years, their personal and historical aspects and the role of art in it. These replies took the form of written responses and also objects, tape tracks, photos, works of art, etc. Here, too, the daily newspaper appeared as an important element available to the viewer. The reading room was also envisaged as an interactive space: each viewer had the opportunity of responding to the artist'squestions themselves, of bringing an object of their own, etc.

Some artists brought even more heterogeneous spaces into the gallery. Janja Žvegelj organised a squash court in the Škuc Gallery (as a response to the unusual shapes and measurements of the gallery rooms) at which she actually played a tournament with the gallery's artistic director. These features should probably have not only been read as ready-made art; they were an about-turn in which the artist (who was not actually a professional squash player) exposed herself, at the same time bringing onto the scene the gallery's art director - an element of power who ordinarily does not perform in front of an audience in such a direct manner. By introducing squash to the gallery the established relations of power were also shifted - at least as long as the tournament went on. And so it is understandable that the artist so strongly emphasised the gallery's institutional framework of her project, even including a ceremonial opening speech.

Some of Darij Kreuh's projects have introduced into the gallery space different kinds of spatial order altogether. At the 2nd Triennial, U3, he thus "exhibited" an object that was completely immaterial, as it was only a spatial segment defined by coordinates in a three-dimensional coordinate system. The coordinates of this object transmitted three different radio stations as part of the signals that appear on radio receivers in such a way that each of the stations transmitted the coordinates of one axis. In a way, the object therefore existed in the gallery space and at the same time was distributed across the immaterial realm of radio signals and information where it became senseless noise. (Not only was the serendipitous radio listener able to see the coordinates of only one axis on his or her display, he or she would be ignorant of the context of these numbers which would thus make no sense to the listener.) The "exhibited object" was presented as the Tower of Babylon, the point when the full swing, differentiation and specialisation of communication systems turned into the opposite - the incomprehensibility and incapacity of communication. Kreuh expanded the theme of entwining different spatial systems, or we could even say systems of reality in a project prepared for in the Kapelica Gallery. Here, through an "information helmet", the viewer stepped into a virtual world while at the same time moving around the real space of the gallery. The viewer thus moved physically in one space while they visually "moved" in another. With the aid of technology, other viewers in a neighbouring premises found themselves in the position of the "impossible" viewer, as they were able, via monitors, to concurrently follow both sequences. On one monitor they observed the movement across objective space and on the other the perception of virtual space.

Up to this point I have primarily spoken about exhibition space and the modification and deconstruction of its established principles. However, it has already been clear in the projects I've mentioned, that the space was defined by its institutional framework, system of values and requirements. An exhibition, in short, is not merely the artefact mounted in a physical space, but also the whole process that leads up to this - the system of selecting, directing and mounting, etc. Some projects are thus directly orientated towards this aspect. Here I will mention two artists, both taken from the most recent U3 exhibition; both projects, each in their own way and independently of each other, dealt with the role of the exhibition selector and curator, who in this case was Peter Weibel.

Nika Špan prepared her Retrospective by explaining projects she had carried out up to that point in time, by drawing for the curator, who in turn observed her in the act of drawing on a television screen. Through a different monitor the artist was able to observe his reactions (he expressed whether or not he understood by nodding). At the exhibition, both recordings were confronted in such a way that from an elevated position the curator observed the artist's hand drawing. This work is obviously concerned with communication (mediated and transformed via media technology), but not merely with anyone - just the selector, who was the curator of the exhibition - and also the element of power. The work is actually a staging of the situation typical of the contemporary art world, in which the artist is continuously obliged to show, describe and explain his or her work.

As her project, Maja Licul exhibited the selection process through which she was selected - a process which, though of such vital importance to the exhibition, is not otherwise visible within it. The artist exhibited the portfolio of her work with which she applied, the letter informing her of her inclusion in the exhibition and the recording of the conversation between her and the curator during which the curator discussed the artists' work with them and anticipated projects for the exhibition and finally decided on their participation in the exhibition.

Here, I must certainly mention the activities of Tadej Pogačar or rather his institution called The P.A.R.A.S.I.T.E. Museum of Contemporary Art. This is an institution which does not have its own premises or art collection, but which acts according to parasitic and parallel principles. This means it moves into a host institution, intervenes and exploits its structures. By doing this it explicates the hidden ideological suppositions on which the activity of the host institution is based and which we consider natural and self-evident. One of the most characteristic interventions of Pogačar's museum was a museum which, among other things, held a collection of African "aboriginal" art. Pogačar placed these works of art face to face with objects characteristic of western rationalism and pragmatism thus developing a critical discourse on the ideological suppositions (for example the idea of cultural differences) which the West takes advantage of to build, maintain and establish a dominant position in relation to the Third World. Pogačar's interventions revealed the concept and structure of the mentioned collection as the result of these ideological mechanisms.

All of the mentioned projects dealt with gallery space which, in spite of its critics and deconstruction's, continues to be very important. However, the most diverse range of other surroundings can emerge as exhibition premises. Unlike the white cube, these do not even seem to be neutral, although on the other hand a public sculpture can also behave as if it does not properly relate to its surroundings (think of the numerous sculptures in pedestrian zones, parks and the courtyards of business buildings, etc.). To intervene in non-gallery surroundings means to step in to or become involved in complicated semantic groups, the principles of day-to-day life, the historical, ideological and institutional contexts and so on. Here I will mention only two examples of many.

The first is a project mounted by Marija Mojca Pungerčar in the French Cultural Centre in Ljubljana. She took the Centre's windows and turned them into shop windows in which she exhibited white Chanel outfits with highly minimalist black decorations. The mounting and lighting of these garments were so effective, that the Centre truly appeared to be a haute couture boutique. It was only after an observer came nearer and took a closer look at the garments that they could realise that these were in fact replicas - very large ones made of plastic. Each of the outfits bore a label with the name of an important woman in French history and the project, appropriately enough, was titled Cherchez la femme. The shop window displays with the outfits were supplemented with a window with quotes by Coco Chanel and ascetic saints (for example Ignatius Loyola) on the value of reserve and asceticism appearing side by side. Inside the Centre, the artist exhibited lounge tables on which she presented the various roles of women through pictures taken from illustrations. All this probably makes it clear that the artist took advantage of the context in which she exhibited: in pursuit of her own interests, no less she dealt here with notions and stereotypes relating to the idea of French culture, the role of fashion in it, the function of women in the representations of French tradition and culture and so on.

A somewhat different project was prepared by Alenka Pirman in the large reading room of the National University Library in Ljubljana. For a long time the artist had collected "Germanisms" appearing daily in everyday Slovene conversation, but which are not allowed in the written or formal usage of the language. (The project, organised in the National University Library (NUK), was only part of a larger process which the artist concluded with the publication of a dictionary of these words. The project was titled Arcticae horulae after the first grammar book on the Slovene language.) On the tables in the reading room she displayed little banners onto which examples of these collected words had been embroidered. (These little banners had an exceptionally homemade appearance reminiscent of traditional primary school "handicrafts".) The location of this project was in no way accidental. The Slovene language is the foundation of the Slovene national identity, so to speak the "Slovene essence of being", and this foundation is most expressively realised in the form of the book. When architect Jože Plečnik designed the library building he emphasised its symbolic function even at the cost of its functionalism. In the architectural designs this symbolic function is most strongly stressed in the line running from the portal via the monumental stairway to the grand reading rooms. The National and University Library is, so to speak, the central temple of the Slovene book, Slovene literature and language and thus the Slovene national essence. So, the artist was introducing into this temple a kind of heterogeneity, a damaged language that has been spoiled, a deformation adopted directly from foreign languages, particularly German. And yet this act should not be seen simply as an anarchic assault on established values; her subversion is actually much more refined. The unusual paradox to which she draws attention lies in the fact that these inadmissible, borrowed words are sensed as something genuine. Whenever we wish to speak directly, "genuinely", in "everyday language" or in the vernacular we can hardly avoid them. Contrary to this we sense the correct usage of the language as something manufactured, artificial or laboured; we do not have the sense of direct and genuine expression from a speaker expressing him or herself in this language, but rather sense a sort of distance between the act of pronouncing and the pronouncement. If, therefore, language is the foundation of our national identity, then registered in the very heart of this identity, where it is most genuine, are foreign languages and foreign identities.

The Curator and His or Her Strategy

Recent developments in art have highlighted the role of the curator as the selector, author of the exhibition, interpreter and co-creator of an exhibition's context. The figure, who within the context of high modernism was analogous to the contemporary curator, was the art critic. He or she would depart from what would seemingly be an objective position yet which in truth concealed the actual partiality or even arbitrariness of his or her judgments and decisions; in this the art critic was truly analogous to the "white cube". The emphatically personal or even arbitrary nature of the work often characteristic of the contemporary curator is actually the deconstruction of the position of power and selection. (Speaking about "deconstruction", I am not trying to say that curators can eliminate their role as the instance of power in the institutional system of the world of art, but rather that they reveal this role clearly and no longer present it as something "objective" or "natural".)

Although there is often talk about curators actually turning into artists, this statement is incorrect. What is actually true is that their role is probably becoming more "dialogical". A "dialogic" relationship signifies that though the curator does not create the works nor defines them (although he or she can have a practical influence on them), he or she can decisively determine the viewpoint from which we observe them, emphasise a particular aspect and so on. By selecting the work the curator is placing it into a certain environment, supplying it with additional information and interpretations, etc. The curator is actually defining the context of the work through which it might acquire an added value, but this context does not also determine how it is received.

The idea of the curator as artist probably appears because in this dialogic relationship the curator can have quite an active role and at the same time because he or she departs from personal preferences, concepts or even obsessions more plainly than before. And this picture also emerges because curators today frequently attempt to avoid conventional forms of presenting art and instead look for new environments, forms and contexts which should provide the art with new possibilities and at the same time would enable a more intense relationship towards these works as a result of their being different and unconventional.

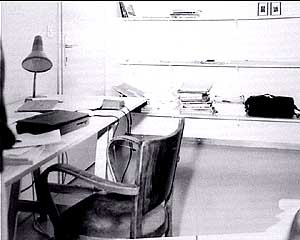

I will try to make concrete or clarify some of these aspects in a project which I have titled Inexplicable Presence and subtitled The Curator's Office. As the subtitle indicates, through this project I have tried to give thought to some of the aspects of the role of the curator in contemporary art. I approached the project by sending eleven artists a copy of a photo showing a particular place in Ljubljana and a brief text explaining why I chose the place in particular. The photographed place is tied to a very personal, and yet expressly marginal experience of mine. But as often happens, this marginal experience has been unusually permanent. I asked the artists to create a piece which would somehow stem from the photo and text. With the exception of the request that the work be a response to the picture and story, I did not want to determine the motif nor the medium of the artists' work. The only limitation was that their work was to be sent to me by post.Of the eleven artists, ten responded positively, nine of whom actually sent me their work. These were Lewis Baltz, Jože Barši, Jochen Gerz, Angela Grauerholz, Per Kirkeby, Yuri Leiderman, Mladen Stilinovi}, Uri Tzaig and Heimo Zobernig. (Suchan Kinoshita chose not to send me her work because she was not pleased with it, but I nevertheless counted it as part of the exhibition as an "absent piece".) The works I received were extremely diverse; they were mainly not only direct, impulsive responses, but in some cases very carefully conceived pieces which were, of course, small in format and in their outward appearance often closer to studies than exhibition material. I then prepared a sort of exhibition with these pieces. The chamber-like and partly study-like character of the works required an appropriate space. For this reason I used a room located right next to the underground exhibition rooms of the Ljubljana Museum of Modern Art which are ordinarily not used as exhibition areas. I moved my office there (for two weeks) and built a kind of personal space with these works. Everyday I spent several hours in the space carrying out my daily assignments; of course I was prepared to speak to any visitor who desired to.

Through this activity, I slowly discovered how important not only my general discursive points of departure and world outlook were to my projects, but also my personal reactions (sometimes vague and uncertain), memories, and what a major role coincidence plays. In the role of the curator itself, I am increasingly attracted to the peripheral, ephemeral, accidental and general. I am fascinated by the traces of fleeting thoughts and transient feelings which sometimes (not always, even less frequently so) linger on as something curiously permanent and which can have far-reaching consequences. This of course does not mean that I have anything against large-scale projects and major exhibitions and I am definitely not of the opinion that these should be "replaced".

It is just that I am particularly interested in the possibilities of marginal fields of art, attention, etc. A significant aspect here (which was also tied to all the other aspects) was the issue of the opportunities offered by low-budget projects. (The entire project was very low-cost and set out in such a way that I was able to manage it myself.) I am convinced that a conscious exploitation of the possibilities of a project like this creates specific qualities which large-scale and costly projects cannot offer.This is why I was interested to discover whether it was feasible for a project which would really be founded on a very private and marginal point of departure to nevertheless develop a dialogue. I decided to begin with a little personal experience as described. I opted for this point of departure because I believe it contains issues that strongly interest me: the decisive influence of something I do not understand and the permanence of an ephemeral experience and its influence on comprehension, understanding and assessment. Of course, I do not consider my personal obsessions, preferences and similar things important enough to justify such a project in itself. Moreover, I do not consider them to have been their centre, but rather merely a point of departure; above all I wanted to unveil a specific field, an active interactive space for works of art. I therefore did not appropriate the role of the artist, but merely posed a question and problem while at the same time striving not to conceal the circumstances of my own position.

To be sure, I was also faced with the question of which criteria to apply when it came to deciding which artists to ask for cooperation. I was convinced that these criteria were an essential aspect of the overall project and that they should, in a way, be tied to its initial ideas. That is why I invited artists who above all were important to me personally (that is to say I do not only objectively consider them to be good artists, but I am also personally drawn to their work), whereby my attraction to their work is linked to the fact that it contains something which I do not fully comprehend or understand. The invitations were therefore not a "selection" based on a "concept"; they were meant to be direct and personal. This is why I did not share with the artists the list of the other invited artists, but rather in addition to the photo, story and description of the project I included a personal, handwritten letter in which I explained which aspect(s) in their work I found particularly fascinating and why I chose them in particular.

An aspect, which in view of the overall project seemed highly important to me, was how to establish an environment for a more intimate and attentive relationship towards art. As a possible model of such a surrounding I envisaged the position we findourselves in as visitors to an office or study and observing the works hanging there. It is more likely that in this case the works would be drawings, sketches and smaller pieces instead of real "museum pieces"; but the smaller distance and more personal relationship towards them can encourage a more attentive investigation, contemplation and discussion than can be triggered by large, major pieces hanging in the museum halls. And yet, again, this kind of discussion is ultimately merely an episode, an ephemeral event which nevertheless can sometimes have more permanent consequences. In the museum surroundings I was, of course, able to establish a space that was only partly private and partly public (after all this was a kind of exhibition and not a private visit); but as discussions with the visitors indicated the environment was stimulating. It was highly stimulating for me, too; in the hours I spent there and in the conversations with the visitors I returned to the exhibited work, studied them and discovered always new dimensions.

The Changes to Institutional Settings and New Opportunities of Exhibition Sites

Institutions played a role in all these shifts. The changes within the institutional setting span from the more or less cautious relativity of the museum's role as selector and enforcer of hierarchies via ideas regarding the museum and exhibition space opening up to the social and natural environment, its contradictions and changes (in program and approach as well as in terms of architecture) to the new roles being assumed by the specifically non-institutional "institutions" and spaces which in the nineties have acquired a special place or status within new constellations.

Over the past decades criticism of the "white cube" and equivalently to the museum and exhibition institutions has taken several routes and in many ways current institutional practices stem from these findings. A critical route has been directly orientated toward the supposed objectivity and neutrality of the traditional premises/institution; these authors and writers have, for instance, drawn attention to the ideological or even concrete political backgrounds of the supposed neutrality of institutions, to the social functions of the selection and presentation mechanisms, and so on. On the other hand, the fact that art itself began to consciously place itself in concrete spaces with concrete social, historical and aesthetic dimensions could not help but have an influence on institutions.

These and similar tendencies have shaped the institutional structure of the "world of art"; the formerly rigid pyramid, hierarchic structure has become much more open. On the one hand, possible areas in which to exhibit have even increased, and on the other, museums and galleries are now seen as functional components of a kind of societal entity, its internal conflicts, domination systems, etc. Needless to say, this does not mean that institutions are no longer the centre of power and point of codification. However, this codification is not the same as physically bringing art into an institution's exhibition space anymore. It actually occurs in a wider field in which "marginal" scenes can also be incorporated. Moreover, institutions themselves are spreading out to scenes such as these and appropriating them. At the same time, an opportunity has opened for specific exhibition sites or institutions which no longer appear as something strictly alternative, marginal or pushed to the side, but are rather comprehended as key component of the art field.

I can illustrate these shifts with several examples taken from institutional and non-institutional spaces. It is thus possible to observe a tendency towards a "dialogic" relationship towards artistic tradition in the museum practice of the Ljubljana Museum of Modern Art. This is probably best seen in the arrangements for retrospective exhibitions of the key artists of 20th century Slovene art which are far from neutral. On the contrary, these arrangements actually emphasise the historical distance, the aspect of interpretation and appropriation as well as the tendency to breath new life into the works on view. The mounting of exhibitions such as these are, as a rule, entrusted to contemporary artists (exhibitions have thus been mounted by Jože Barši, New Collectivism and Tadej Pogačar) who are expected to establish a dialogue with the historic pieces, add their own commentary, place them in a new light and shed further light on them, etc.

In the Slovene art scene of the nineties a number of specific spaces have created their own profiles with expressive programs and their own "styles" and these have ranged from the more or less established galleries to different media centres and alternative sites. I will mention here two very specific exhibition sites or "institutions", sites which in their very concepts and practices are highly characteristic examples of exhibition and (conditionally) institutional activities in the open and diffused space of the nineties.

One of these is Vila Katarina - a private residential house with a garden. For ten years now the owner, Mrs. Milena Kosec, has prepared exhibitions and other events. The dimension for which Vila Katarina is certainly relevant in the context of the nineties is that it does not put itself forward as an "alternative" or "underground" space in its program. That is to say, it does not define itself by contradicting institutional and established practices. On the contrary, this is a project where personal interest has been teamed with the utilisation of the specific possibilities offered by the premises itself. The fact that this is a private, residential premises creates a particularly intense relationship with the artists themselves who must adapt their production and mounting to the special character of the space as well as the viewers.

Another highly specific space is Sestava which operates in premises within the former military barracks on Metelkova Street in Ljubljana. Sestava can be seen as a unique exhibition space and at the same time as a continuously developing project, a discussion (Sestava's key component is an area allocated for discussion both within the group's members as well as other interested individuals) and an attempt to establish an open social space. The Sestava project derives from deliberations about the building it inhabits - a former military prison. The project's initiators had the idea of taking this space with its traumatic connotations and transforming it, but not by erasing its historical dimension. Their idea was to change the prison cells into the rooms of a youth hostel by giving the individual rooms to various artists who, departing from their own experiences and interests and contemplation of the space itself, would establish habitable space.

Photos:

- Miroslaw Balka, Winterhilfsverein, 1994, installation in Mala galerija, Ljubljana

- Rikrit Tiravanija, Brez naslova installation at the exhibition "House in Time", Moderna galerija - Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana

- Rene Rusjan, Reading Room, 1997, installed at the "2nd Triennial of Contemporary Slovene Art - U3", Moderna galerija - Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana

- Alenka Pirman, Arcticae Horulae, nstallation in the National and University Library in Ljubljana, in the context of the "Urbanaria" project, Soros Center for Contemporary Arts Ljubljana, 1995

- "Inexplicable Presence. Curator's Working Place", Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana, 1997, installation view