Nadja Zgonik

The Role of National Identity Research in Theories of Display in Slovenia: Between Past and Present

|

In contemporary

art, national identity research is highly unpopular. A modern scientist

from the field of art history does not want to be publicly presented as

a researcher whose work contains notions such as national art, the spirit

of the space and art heritage. Nevertheless, the notion of identity and

related research has been gaining in significance. It is connected with

increased interest in special social groups which have for different reasons

been pushed to the edges of the society. These groups comprise black people,

women, homosexuals, south Americans in the USA and those mentally and

physically different from the rest of us. This new interest is obviously

connected with the desire to pay equal attention to those sections of

the global society which have so far been ignored or neglected for various

reasons, the most important being that these groups have never possessed

capital nor been in power.

A small nation is also a special social group which up until the moment

it forms its own state has no real political power or influence and no

true possibility of establishing itself culturally. Even after founding

its own state, a small nation finds it difficult to assert itself amongst

big nations which are in the leading role(1).There

is no reason why the identity of a small nation could not be viewed in

the light of the currently topical research of the identity of marginal

social groups. Moreover, because of its significant theoretical heritage,

the research of a small nation's national identity, which has always been

asserted in the sphere of culture, can assist us in forming contemporary

theories in the research of the sociology of marginal social groups.

In 1994, or the third year of the independent Slovenian state, an exhibition event was introduced with the aim of following and presenting national artistic situations. It was entitled The Triennial of Contemporary Slovenian Art or U3. (A similar event was introduced during the time of the Fascist Italy. Namely, in 1931 the first Quadrennial of National Art opened. In the catalogue of the first exhibition, Ardengo Soffici wrote about the "Italian artistic genius", pointing out that the aim of the exhibition was to "give Italy a new kind of art which will be alive and will suit the period of the civilisation presently in the making." While the first Quadrennial was at least on the surface a non-political event, the opening of the second event was attended by all important politicians of the country, including il Duce.)

Naturally, the question remains as to what extent the decision to define contemporary national art using the U3 exhibition was intentional and conscious and whether the exhibition's intention was in fact to create a panoramic presentation rather than a possibility for classification and interpretation. It is interesting that, when the event was first introduced, nobody was disturbed by the fact that with the presentation of the nationally limited artistic production, Slovenia renounces the international context of art, thus automatically drawing closer to the definition of national art. The first Triennial of Contemporary Slovenian Art was prepared by a Slovenian selector, Tomaž Brejc, and it offered an overview of some of the leading and also lesser known, both old and young, visual artists, which was a reflection of a personal but simultaneously objectivised perception of the Slovenian art scene. The event therefore presented the contemporary situation in art and was not aimed at drawing any conclusions in that regard.

This problem became even more obvious during the second triennial which took place in 1997. At the time, the Modern Gallery invited Austrian critic Peter Weibel to act as exhibition selector. Weibel justified his selection in a short text: "The aim of this year's U3 Triennial is not to search for a cultural identity, for a nationally definable art or for Slovene art ..." However, he concludes in a completely different tone: "Medialisation, contextualisation, the return of the real and care for the social - the decisive strategies at the end of the 1990s - ensure that aesthetic and historical experiences do not become separated. Historical experience prevents the works from falling into an ideology of false neutralist internationalism which is, in fact, the worst expression of colonialism and hegemony; rather, the works represent a specific contribution (from the point of view of artists based in Slovenia or with some relation to it) to aesthetic questions of international relevance." It is true that Weibel does not use the expression national identity, but what else could the specific contribution of Slovenian artists to the international situation be?

The notion of identity connected with a specific national space thus emerges in all its controversy. But before we venture into the history of Slovenian art in order to shed light on the role and significance of national identity research at all levels of forming important art institutions ranging from criticism, galleries, art collections and museums to the concept of national history, we must define what the notion of the nation actually entails if we attempt to introduce it into art history using the methodology of art geography. The notion of art geography was first used by Kurt Gerstenberg in the title of his work Ideen zu eine Kunstgeographie Europas in 1922. With this term, he wanted to denote the explanation of art in terms of the geology and morphology of the terrain. He proposed that art maps be compiled so as to make it evident that political borders differ from the borders of art. According to Gerstenberg, Europe should be divided into optical zones arranged from north to south and the map would clearly define the art influences and the transitory role of leading artistic nations.

In 1933, during the 13th International Art Historian Congress in Stockholm, art geography became a real theoretical fashion trend. The main topic of the congress was defined as follows: "When in the art history of a certain nation can the national character be distinguished for the first time or in some particularly interesting way?" In art history, the thirteenth congress is known for the escalation in the nationalist tendency of German art historians who were increasingly serving the purposes of German policy. But, the new methodology of research into the problem of the bond between the nation and its artistic production, which was only still in its beginnings, while the dominant theory of the time was the milieu theory or research into the spheres of artistic influence, was developed by experts enabled by the new approach to present marginal and unknown art spaces and to find them an equal place in art history.

The most important work which offered an overview of research results achieved with the help of the new methodology was Kunstgeographie, Versuch eine Grundlegung by Paul Pieper, which was published in 1936. The author explains that the aim of art geography is to shed light on all issues connected with the spatial notions of art history. Art history attempts to follow invariables, constants, time or schools. All this can be recognised in spatially interconnected art works, for space connects them beyond the dimension of time. Pieper suggests that the notion Raumstil (style of a space) should be used along with the notion of Zeitstil (style of a time), for it represents what is constant and unchanging and what can be explored in art to the extent that although we do not know anything about a work of art, it is possible to classify it within the framework of the style of a certain space. These findings must be expanded with the findings of cultural geography, in order to create a meaningful whole, the main characteristic of which would be the category of space as the opposite of the category of time.

Because of its specific characteristics, art geography became the most influential methodology when Slovenian art was being assessed. The first synthetic scientific attempt at forming a Slovenian history of art was made in 1922, when Slovenian representatives of art and culture in general, including the two art historians Izidor Cankar and France Stele, gathered to plan the Historical Exhibition of Slovenian Painting. (All exhibitions with a historical context prior to this one were organised by artists. For example in 1910, in his own exhibition pavilion, Rihard Jakopič set up an overview of eighty years of Slovenian visual art.)

According to Izidor Cankar, the most important achievement of the 1922 exhibition was the realisation that it was possible to speak about a specific recognisable character of Slovenian art: "Speaking about the Slovenian component in art, we must first answer the question whether art in Slovenia displays anything that is different from the art of other nations, anything specifically Slovenian. The historical exhibition undoubtedly answered this question by showing that at least from the 18th century onwards, Slovenian painting cannot be labelled Italian, German nor anything else, for it contains something authentic. Neither it can be termed Carniolan painting, for it goes beyond the borders of individual regions. This painting is Slovenian, because there is no other way to call it. This is one of the most important and most beautiful results of the historical exhibition, not only because it is a new theoretical finding, but also because it is an important fact for the education of the nation."(2)

This exhibition led to the 1924 publication of the first scientific historical overview of Slovenian art, entitled Oris zgodovine umetnosti pri Slovencih (Historical Overview of Art in Slovenia) by France Stele. As at the exhibition, artists discussed in the book are both the creators of top artistic achievements and those formed in a small undemanding cultural environment, who worked in accordance with the unambitious expectations of their patrons. Since this artistic position is a good illustration of the situation in Slovenian society at a certain historical moment, it must equally be included in an overview of artistic development.

So, in art history, what is the reason for the emergence of criteria which no longer render the notion of artistic quality in terms of certain stylistic elements absolute?The reason for this can be found in the neglected majority of art production and certain excluded geographic (and therefore national) spaces from the universal history of art.

The reason for starting research into the specific role and function of art in a small nation must also lie in the fact that whenever we leaf through a general overview of world art, we wonder why none of the presentations of past art historical periods include artistic works from our local environment. The same question crosses our minds when we browse through the shelves of large international bookshops, searching in vain for a book on artists from small nations, for they contain only books on artists who are representatives of large national groups. If we came to terms with the explanation that the reason for this is the absolute and normative quality of artistic creativity, we would also come to terms with the automatic placement of our own national production on a lower level.

Since there is obviously a difference in the assessment of big nations leading in the sphere of art and smaller ones which have still not won their place in the creation of world artistic production, we must seek the explanation for this in the relationship between art and the nation. In order to avoid being caught in the whirlpool of archaic and primitive nationalism, let us first examine the explanations of nationalism by the contemporary school of sociology and political science. Ernest Gellner, a great contributor to the better understanding and more realistic assessment of nationalism, sees nationalism in two forms, as negative and positive. The former can mostly be found in large nations and in moments of threat and humiliation, it can be taken on the dimension of a violent and militant movement. The latter, which is positive, can be found in small nations without political sovereignty, which on their path towards independence rely on their culture. A small nation uses culture as proof of its right to exist, for it must convince others that it is special, different and authentic (in other words, that it does not belong to anybody else but itself and that, due to its own special characteristics, it cannot be made to merge with any of the large, already existing and recognised units). It must be pointed out that the understanding of nationalism as a positive ideology was greatly contributed to by new definitions, in terms of which national identity is understood as a thought construct, as something dynamic which can change with time and not as something basic, final and transcendent. Or, in the words of Gellner: "Nations as a natural, God-given way of classifying men, as an inherent ... political destiny, are a myth; nationalism, which sometimes takes pre-existing cultures and turns them into nations, sometimes invents them, and often obliterates pre-existing cultures: that is reality."(3)

Therefore, the "Slovenian cultural syndrome" (coined by Dimitrij Rupel in his discourse on the history of Slovenian literature from Prešeren to Cankar)(4) no longer seems to be only Slovenian, but rather a syndrome of small nations.

But what is specifically Slovenian is that before the emergence of political awareness of the significance of culture as the a pillar of demands for a national state, these ideas were developed by artists. Here we find another distinction: big nations justify their existence with their glorious history of conquest and state-forming acts and are therefore called "state nations" (Staatsnation), whereas small nations which have not won any important victories base their claims on culture (Kulturnation). For this reason, in small nations, we encounter cultural nationalism which can exist even before the emergence of developed political awareness and which can be termed pre-state ideology.

Slovenians have neither our own glorious imperialistic history nor great rulers and generals who could be transformed into national heroes for contemporary use. This problem, which at first glance does not have anything in common with visual art, was dealt with by painters and sculptors in the period when political expectations for a large heroic national picture emerged. A new motif had to be 'invented', for artists could not rely on transparent history to justify the significance and glory of the nation's past. Once again, painters drew from literature. Let me better define the difference: it is not that Slovenian historical science was less developed. Historians did research national history and wrote books about it. Nevertheless, the scientific records of history and popular awareness are two different phenomena. Only on this second level of the forming of common awareness, in which the decisive role is played by the educational and information system, a generally acceptable hierarchy of past values emerges.

This popular awareness as a form of general national awareness was formed by Slovenian literature prior to the forming of all levels of education in the native language and all national institutions. The most frequently treated national history motifs in literature gradually settled down in national awareness as scenes illustrating the most famous events from the nation's past. For the development of historical painting in Slovenian art, two public tenders to create paintings on themes from Slovenian history are crucial. The first was issued in 1938 for the decoration of an interior wall in the main corridor of the provincial palace - the present-day building of the Slovenian government. The historical theme could be selected by the artiststhemselves and since none of them had ever worked in historical painting, this proved to be a highly complicated task. The selected motifs were as follows: six paintings of the Arrival of St. Ciril and Methodius to Pannonia, five paintings of the Inauguration of the Caranthanian Prince in Gosposvetsko polje, five paintings of the arrival of Slovenians in their new homeland or at the sea, four scenes from peasant uprisings, one image of a Turkish raid, a portrait of Napoleon, Trubar and King Matjaž (Matthias Korvin), the inscription "Buge vas sprimi, kraljeva Venus" (in ancient Slovenian, meaning "May God receive you, royal Venus.") and for the spaces above doors, images of Hren, King Matjaž and the Turks(5). It is interesting that as national heroes the images of both the leading representative of the Slovenian reformation movement and the person responsible for quenching the movement were proposed. The second public tender issued in 1939 did not result in any greater creativity and originality. Historical themes simply could not root themselves in Slovenian painting and the collections of the National Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art do not include any works of art of historical content, not even with national symbolical figures.The feeling of alienation from historical themes in visual art is easy to explain. In awakening cultures, the ideal moment for their realisation came in the second half of the 19th century, in the art period of realism when, following classicist patterns, small national cultures began to explore their own history instead of Antiquity. Slovenians missed this moment and in the 20th century, historical motifs could no longer be reconciled with the modernised vision of a painting's structure.

It is interesting that Ivan Grohar felt that the dilemma whether to paint historical themes or not was a matter of intimate choice, for at the moment refused a commission for a historical painting, which according to the client was the only opportunity to make the painter famous, he started painting Spring instead(6). Jakopič formed his opinion about "large-theme" painting on the example of a painting entitled Slovenia Bows to Ljubljana by Ivana Kobilca. In his article published in the Ljubljanski zvon journal, he described this form of art as outdated and associated with a certain social stratum which it served as a means for expressing their spiritual bareness. "Allegory has been mostly used for advertising and propaganda purposes particularly in the time of spiritual weakness of the ruling class and misunderstanding of the purpose of art. It is a result of an unnatural shallow pleasure, luxury, saturation and egocentrism ... One who does not share historical feelings but lives in the present with his body and soul finds it difficult to walk back to that wanton past which shares nothing in common with the present. He finds it difficult to suppress his yearning for knowledge."(7)

Slovenian impressionists, particularly the two leading representatives, Jakopič and Grohar, opted against the historical genre and in favour of the landscape. If we connect this dilemma with the already mentioned duality of history and nature as two different possible spaces of the identification of a nation, the artistic decision of Slovenian impressionists to paint landscapes can be seen as an organic part of a global conceptual context of a nation which justifies its existence through the natural law, its own language and culture.

It is of utmost importance that national identity is created at points of departure which are created in the present with the help of the past. This distance helps us to change them by means of selective memory. In other words, this process is called the mythicization of history. In humanities, this process began at the high-point of German romantic philosophy in the late 18th century in the Jena circles of Schlegel, Hölderlin, Hegel and Schelling. Germans explored the classical past, exposing its two sides: the classical and archaic. The classical, which includes the Hellenic or Italian expression, had been adopted by the French. The archaic had remained unused and was therefore adopted by the Germans. It is dark and mythical. The myth opens up the issue of mimetics, for only mimetics makes identity possible. In contemporary French historiography, the notion of national identity was replaced by places of memory (lieux de mémoire). Accordingly, memory is contained in a space or region as a geographical unit. This understanding originates from Antiquity, as from the Renaissance onwards, the artist has been equating Antiquity with nature. This equation was also made possible by the fact that in the Renaissance, classical works of art were still buried in the ground and were therefore literally given "birth" by Mother Earth or Gea. For this reason, a homeland is usually personified by a female figure which generates its own culture in the same way that it yields the fruit of the classical past from the earth.

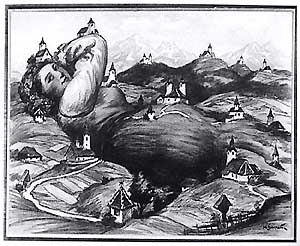

Female personifications of either the city of Ljubljana (8), which represents the queen-bee of all Slovenians, or Slovenia can first be found in the second half of the 19th century. The earliest such rendering of the Slovenian nation in the form of a female body is probably a silver ink well which was, according to an inscription on a shield held in the left hand of the enthroned personification of Slovenia, given to Bleiweis as a souvenir for "twenty years of his service as the editor of the Novice journal by Slovenians from Carniola, on 5 July 1863" (9). There are no personifications of Slovenia in painting or graphic art. Several examples only appear in, particularly, political caricature.We find a less illustrative although artistically more convincing motif when the artist equates the beauty of a landscape with the beauty of a woman, therefore giving a landscape painting the shapes of a female body. This stems from the archaic equation of the fertility of the land with the fertility of the woman and, at the same time, from the tendency to idealise if not actually deify local nature. Several examples of this anthropomorphisation with a special feminine emphasis can be found in Gaspari's work. For example, in the image entitled Our Beautiful Homeland from 1938, the body of a sleeping girl blends with the contours of the landscape and is scattered with typically Slovenian small village churches. It is interesting that a similar manner of depiction is preserved even within the context of a more advanced expression in painting. Both in Istrian Land by Boris Kobe from 1954 and Terra rossa by Marij Pregelj from 1965, the female body personifies a specific, Istrian, landscape.Since the origin of this kind of mentality cannot be precisely defined and since we can only explain it in terms of archaic, primitive beliefs, it is of great importance that such examples are not only the results of the popular thought, but that in a primitive formof an ancient primeval memory they can also be found in the works of spiritual and intellectual artists. Here, I wish to quote a statement by Ivan Prijatelj which confirms that this kind of attitude was generally widespread. In addition, it reveals that it may have been a result of a special emotional excitement. "In front of a painting by Grohar, I want to cheer like some Slovenian village boy. For Grohar is a Slovenian farm boy and this is beautiful beyond description. He is head over heals in love with his girl. And Grohar's girl is nobody else but Slovenia's nature: a healthy red-cheeked lass with a motley apron and so many skirts that colours, flowers and folds cannot be counted."(10)

A similar emotion which borders on passion also connects the expressionist painter France Kralj with the local landscape: "Oh, the hilly horizon of my home valley, how expressive you are! The elementary force which made you swell is contained and offers itself directly; there is no secret in your heights nor your slopes - the secret is in yourself. From yourself, you create and give. You are an image of a full, strong body of a sleeping goddess."(11)

A

logical result of such contemplation was The Sower (12),

particularly as depicted by Grohar (13), who

therefore made an important contribution to Slovenian art history. When

the painting was displayed for the first time, at the 1st Art Exhibition

in Trieste, its significance was determined as follows: "This painting

must become the most popular painting of our nation, for in it, one not

only sees a piece of our rural life but also a reflection of our soul,

our very being. From this morning fog, the sound of the sower's heavy

stride and a quiet melody of a sad folk song seem to be seeping into one's

ear."(14)

A

logical result of such contemplation was The Sower (12),

particularly as depicted by Grohar (13), who

therefore made an important contribution to Slovenian art history. When

the painting was displayed for the first time, at the 1st Art Exhibition

in Trieste, its significance was determined as follows: "This painting

must become the most popular painting of our nation, for in it, one not

only sees a piece of our rural life but also a reflection of our soul,

our very being. From this morning fog, the sound of the sower's heavy

stride and a quiet melody of a sad folk song seem to be seeping into one's

ear."(14)

With The Sower, Grohar gave Slovenian art a painting in which he succeeded in ideally merging nature and man, whose life depends on nature. This bond is mutual, for nature will bear fruit only through human work which ennobles it. The Sower is a male figure who receives the attributes of fertility from nature. Nature as a space or a specific environment and its personification become one.Also because of this bond, the paradoxical situation which appeared as a seeming impossibility of connecting the modernist, cosmopolitan and international painting and the homely character of paintings by Slovenian impressionists could be surpassed. In the review of the 1st Yugoslav Art Exhibition in 1904 in Belgrade published in Slovenski narod journal, this paradox was described as follows: "Grohar's paintings are completely modern, nevertheless, they radiate a powerful homely spirit. Although Grohar gave in to the modern artistic outlook, which usually completely separates the artist from his homeland and breaks all ties which connect him with the soil, he succeeded in preserving artistic originality and independence. And this by itself proves that it was the will of God for Grohar to become an artist. What has been said about Grohar also holds for Jakopič. His paintings also breathe the fresh homely breath, although they are created in the modern style."(15)

Grohar's Sower has preserved its artistic significance to the present time. In 1991 a radical art group, Irwin, selected its motif to challenge forty-three artists from the entire Yugoslavia. This was the last group exhibition of artists from the former Yugoslavia.

The problem of identity is the problem of originality which becomes recognisable once when it can be distinguished as different to other, already known phenomena. It is a specific character, a difference which can easily be a product of an exceptional individual who has risen spiritually above the general situation. But this individual can develop all his creative potentials only when working conditions are ideal and when he does not have any economic, social or political problems. For this reason, in certain periods of development this specific character can simply be defined in terms of the historical, social and cultural contexts. The research and rational understanding of the cultural context enable the freeing of the notion of national identity of its historical burden and its incorporation within contemporary cultural and historical currents.

Notes:

(1) I do not use terms such as small nation, big nation or leading nation as quantitive definitions, but as expert terminology of political philosophy. The theory of the small nation was greatly researched by the Czech philosopher and statesman Tomasz G. Masaryk, who is also its author. The expression leading nations was coined by Marx to denote those big western European nations which claim the entire western history and sociology fot themselves.

(2) Izidor Cankar, Zgodovinska razstava slovenskega slikarstva, Zbornik za umetnostno zgodovino, II, 1922, 2, p. 134.

(3) Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983, pp. 48-49.

(4) Dimitrij Rupel, Slovenski kulturni sindrom, Sodobnost, XXIII, 1975, 2, pp. 97-109. This phenomenon is also discussed in a book by Rupel entitled Svobodne besede. Od Prešerna do Cankarja. Sociološke študije o slovenskem leposlovju kot glasniku in pobudniku nacionalne osvoboditve v drugi polovici XIX. stoletja, Koper, 1976.

(5) The topic is discussed by Emilijan Cevc in Kmečki upori v likovni umetnosti, Kmečki upori v slovenski umetnosti, Ljubljana 1974, pp. 157-175. A detailed description of the tender is given by Rajko Ložar, Zgodovina Slovencev in naša upodabljajoča umetnost, Kronika slovenska mest, VI, Ljubljana 1939, pp. 28 sq.

(6) I quote: Janez Pirnat, Slovenska oblika impresionizma v delu Ivana Groharja, Problemi, 1964, 14, pp. 177-191; 15, pp. 330-342, quotation taken from p. 330.

(7) Rihard Jakopič, Slovenija se klanja Ljubljani, Ljubljanski zvon, XXIII, 4, 1903, pp. 252-253.

(8) The most famous although not the earliest example is Kobilica's enthroned Carniolan girl who personifies Ljubljana in the scene of Slovenia's bowing to Ljubljana. The Personification of Ljubljana as a Slovenian girl clad in the Carniolan traditional costume and saved from the German green dragon can be found in Brenclju, XIV, 1882, 8.

(9) A photograph of the ink well was published in the catalogue Dr. Bleiweis in njegov čas, Gorenjski muzej Kranj, 1996, p. 96.

(10) Ivan Prijatelj, Dunajska secesija, Slovenski narod, 1905: 70, 27. mar.,pp. 1-2; 71, 28. mar., p. 1; 73, 30 mar., pp. 1-2; 75, 1. apr., p. 1; 76, 3. apr., p.1.

(11) France Kralj, Moja pot, zbirka Slovenske poti, Ljubljana 1933, p. 3.

(12) I wrote about the numerous repetitions of the motif in Slovenian art in the article: Sejanje kot metafora in slovenski kulturni prostor - izbrani primeri, M'ars, III, 2/3, pol.-jes. 1991, pp. 37-47.

(13) Tomaž Brejc, Groharjev Sejalec, Slovenske Atene, Premikajoč se po polju slovenske umetnosti kot sejalec, Moderna galerija Ljubljana, 1991, r. k., s. p.

(14) -avi- , Kaleidoskop: Nekaj reminiscenc s I. slovenske umetniške razstave v Trstu, Slovenec, XXXV, 278, 2. dec. 1907.

(15) Slovenski narod, 22. sept. 1904.

Photos:

- Maksim Gaspari, Our Beautiful Homeland, 1938

- Ivan Grohar, Sower, 19073. Boris Kobe, Istrian Land, 1953